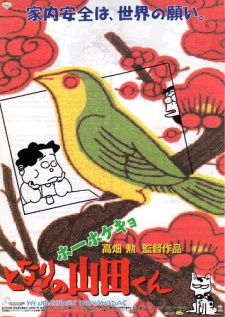

If you grew up in Japan in the late 1960’s and had a TV, there is a 90% chance you still turn it on at 6:30 every Sunday with your family to watch the classic family comedy Sazae-san. The turn of the 80’s saw the true birth of Doraemon as an long-running kids classic, and between 1990 and 1995 both Chibi Maruko-chan and Crayon Shin-chan had joined the canon of short episodic comedies that would gather the parents, the kids, the grandparents, and everyone else around the TV once a week to watch their favorite fictional families flit with mischief and complete anarchy for 30 minutes apiece. To understand the extended family and its power dynamics is to understand early anime and its rise to popularity, and to understand postwar Japanese life in some small way. And it was in 1999 right before the rise of both the new millennium and the new family life in the internet age that Isao Takahata, the most traditional and Japanese of all anime directors, brought his take on the family comedy to the table with My Neighbors the Yamadas, which some including myself would consider the greatest of them all.

A hallmark of the earlier family shows was a childish hand-drawn style, which partially reflected the time period and partially drew the family together for its warmth and blatant comedic misrepresentation of domestic life, a trend taken to the absolute boundaries of absurdity by Takahata with literal pencil drawing on a parchment-colored background and the bare minimum of color necessary. Character designs have squat proportions, cars are boxes, and the poor dog looks completely starved. It is a marvel of illustration that such “crude” drawings give us a real impression of depth, space, time, and in general life, but to pretend that this style is lazy is dismissive to the care that goes into rendering each scene in a perfectly familiar way even in spite of the huge artistic restrictions. The characters are barely recognizable as human, but they appear so at home in their bizarre environment that one paradoxically wonders if the characters could have meshed with the household in such a natural way if the whole thing were a live action.

There is something inherently perfect about anime’s ability to render minor details that make a film great. In his earlier work Grave of the Fireflies, Takahata intentionally avoided animating the constant minute breaths of the protagonists, giving them a deadly still and quiet that when isolated made them appear as if they were statues or corpses. When we come to My Neighbors the Yamadas, there are scenes where everything in the scene stops and stays perfectly still. The music cuts out and the characters are left completely stranded, as if the situation has literally removed them from their actual lives. Due to the way in which the movie is separated into vignettes, they often get no chance to recover before they are whisked away into a completely new point in time, and for us it is as if they had to be reset by some higher power after their last comedic encounter rendered them comatose. No matter how funny a joke that occurs on a sitcom, the best the characters can do is freeze and stare, but even then we see their minute breaths as they absorb the joke. The Yamadas are completely incapacitated by it.

And the jokes themselves are absolutely hilarious. The mother and father of the family love each other and understand each other to the point of virtually being telepathic, and of course they utilize this to fight and one-up each other at every turn in a perfect back-and-forth volley of power. The grandmother also dips in to assert herself as the true matriarch of the family, but often it is her forgetfulness and laziness that ultimately put the bickering couple in their place. Their son seeks to escape his studying and forced interactions with family at every turn, and here we catch a glimpse of Takahata’s frustration with the growing trends of technology and the increasingly brutal competitive culture in middle and high school. Much of the story itself is told by the youngest daughter, who sees everything—from being abandoned in a shopping mall to every aspect of her deranged domestic life—in a positive light, and while she may be insufferable to her parents at times, she is our adorable narrator who gives lets us see the love between the family members despite all their stupid strife.

Because the film is rooted in its comedy at every single moment, this love is extremely subtle at times, with no moment of redemption or moral to tie up most of the vignettes and only bits and pieces of dialogue or spacing to indicate a deeper connection. The older generation would recognize these as classic family dynamics, particularly in the more rambunctious area of Kansai, where the story presumably takes place due to their dialects. Kansai is the more lively, talkative, and comedic half of Japan, and a Japanese comedy would be remiss without the Kansai dialect percolating through the dialogue completely. It also has the feeling of boisterous conversations and a more combative style of interacting with relatives, all of which appear in all the traditional forms of Japanese comedies and particularly when talking about family. The difference is that we never get a true comedic narrator, who brings their bias to the situation. Here the forces at play all have both a loving family and a desire to completely get the best of said family, but in the end there is no one to proclaim any of them the victor.

The other key component is the consistency with which the individual stories are told. Once or twice a vignette will call back to an earlier incident, and one prop appears at the very last moments of the film to completely blow the audience away with laughter. I can’t remember laughing so hard in years. But there is more than just the comedic references; there are a few moments where for all the hilarity on the screen, we can tell a character is really thinking about the life ahead of them. It is not played up for drama, it isn’t serious, and it doesn’t even come to the forefront of the scene. We just see it and know. And so in the most minute ways, our little family grows emotionally even if they never really seem to mature. In fact, maybe all we need is for them to stay exactly the same, in the way that the families from Sazae-san and Doraemon learn a life lesson in every 10 minute episode and yet stay identical after more than 40 years. But Takahata, in creating a one-off 100 minute film inspired by such long-running giants, has decided that his family will one day move forward, change jobs, get married, grow old, maybe even die. He also spared us the process of it all. With the Yamadas there is too little time to worry about the future, and an endless supply of comedy to be had.