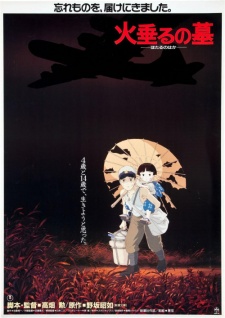

At the height of the Economic Miracle that boosted Japan from a war torn country to a world economic superpower, Studio Ghibli released Grave of the Fireflies, directed by Isao Takahata rather than Miyazaki, hearkening back to the era of war that the youth of the 80’s had never known. It was a distinct departure from the few other Ghibli works before it, containing no real fantasy elements besides the post-mortem narration provided by Seita, the protagonist. It was historical rather than loosely set in the past like Totoro was, but with one shot at the very end of the movie of modern Japan. That single shot, of the Tokyo nightscape’s twinkling lights set behind the dim lights of the fireflies on a hill, was possibly the single most important message the film had to offer. We see many fireflies die, and indeed in this movie they serve many symbolic purposes through death, as the title suggests. And as fireflies die, the lights of modern Tokyo were not meant to last forever. It was a time when youth delinquency were at a peak, and when there was a large gap between the entitlement culture that had been feeding on the anger and resentment since the late 50’s and the generation of children and veterans from the war. And three years later, it was all gone as Japan fell into an economic stagnation like the one of 40 years before.

Grave of the Fireflies, with its tragic depiction of the struggle to survive in the last days of World War II, focused on children, and how their innocence was tested by horrors that no child of any age should be forced to experience alone. It was considered too depressing by many when it was released, and had little commercial success. However, it's distinctly different from the Japanese anti-war movies of its time, and indeed from almost any anti-war film of any country in any age. Throughout the latter half of the 20th century, many allegorical films criticized the emperor’s abuse of the people’s trust and the barbaric waste of human life from the kamikaze attacks, while others lamented the inhumane use of atomic bombs that would forever alter the lives of the residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, claiming many lives and afflicting countless more with disease. There were yakuza and period pieces that called for the end of the honor culture and the family structure of government, while other films were set in modern ports and sites of rapid Westernization, depicting American arrogance and Japanese cowardice.

And yet despite being set squarely in the midst of the war, Grave of the Fireflies points no fingers while still functioning as a profoundly human anti-war film. The American planes are dark silhouettes on the sky, and no American soldier is ever seen. Rather than using these images to make America into a merciless, inhuman enemy, the film regards them simply as a force of nature, not lingering for too long on either their attacks or the immediate aftermath. Not one person blames the Americans during the film. After the film opens we see an air raid siren going off, and the people running to the shelters. Seita, a youth of around 13 or 14, is burying various possessions in the backyard and getting his sister Setsuko ready. His mother casually tells Seita that she will be heading to the shelter, and a short discussion about her medicine ensues. Already we see how accustomed they are to the American invasion planes, and where their priorities lie. They do not know that it will be the last time seeing their house, or each other. The firebombing of Tokyo, often overshadowed by the atomic bombs, was one of the single most devastating attacks during World War II, claiming more immediate casualties than both atomic attacks put together, and irreparably damaging the wooden and paper houses of Tokyo. We see everyone running panic-stricken, and Seita’s face falls, as the attack cuts through his passive acceptance of the American presence. However, the scene quickly shifts to after the attack, and he is now forced to find his mother and keep Setsuko happy.

The most key component to the film’s impact is its lack of dramatics, and how the pace at which scenes shift and move reflects the chaos that Seita and Setsuko have to rapidly deal with as their lives continue on. We see their mother, completely burned and slowly recovering in a hospital bed, and only a few minutes later she is dead. A social worker puts a tag on her arm to acknowledge her death and then sends her out on a stretcher, Seita trying to keep pace with them. His mother is dumped into a pit with the other casualties and set on fire, a mass cremation to avoid the spread of infections. This lasts only a few moments before we see Seita and Setsuko going to find their aunt to live with. At a point that should be a heavy emotional scene, complete with crying and introspection, the movie only can spare a few moments before going straight along. With the mother dead, they have to find ways to survive quickly, and so there is no time for drama.

This may sound like it would diminish the impact, but sad scenes are not where the emotional heart of the film lies. The only moments the movie has to spare on more prolonged scenes are when Seita and Setsuko are playing outside their shelter or eating dinner together, trying to capture brief moments in the midst of all the horror and change of the war to be happy, and to enjoy living. These moments too showcase the unique power that the film has to create empathy with the characters. There are many small details that get put in to enhance the experience of watching a brother and sister playing together, such as Seita going around and around on the monkey bars for a solid thirty seconds of screen time to make Setsuko stop crying, or pulling a cloth under the surface of a bath and popping the bubble it creates—a shot that many critics have cited as one of the first indicators that the film has a true sense of realism and innocence that few films come close to capturing. It's clear that the animators truly understand the world of these children; the children and these small happy scenes have a lot of love and care behind them.

However, the most touching scene for me occurs near the end, when we get a set of small actions by Setsuko, a montage of her cheerfulness and love of life. It's filled with these sorts of small actions, completely unmotivated except by Setsuko’s day-to-day experience of enjoying life. This is where I understood why these children succeed at touching our hearts where so many tragic films have failed: they love being alive, and every action they take reflect this, no matter how dark their futures seem. As we watch their tragic struggles, we too grow attached to these moments, as proof that they still have a reason to try and survive through the end of the war.

They ultimately fail, of course. The opening is a virtuoso sequence of Seita appearing, saying “September 21, 1945. That was the night that I died.” He looks over at a pillar where a boy in tattered clothes lies, hunched over. We instantly recognize it as Seita himself, being ignored or insulted by passersby. One kind person gives him food, but Seita cannot even process this. As he sits there, on the edge of life and death, he finally thinks to himself “What day is it?” before collapsing to the side. A few workers recognize him as dead, calling him “another one”, while also dealing with three or four other corpses near the same pillar. He is completely nondescript in this hallway, just another casualty of the war. One worker finds a tin in his pocket and tosses it out the window, where the ghost of Seita picks it up. Clearly this tin will become important, and indeed it will become a symbol of their innocence and life. But it's empty, and thus to the workers it's a useless piece of trash. That's how easily Seita’s entire life comes to an end, and every trace of his existence is thrown away.

Throughout the film, Seita and Setsuko’s ghosts appear, watching over the progress of their lives. Rather than afford them the luxury of introspection during their lives, they are allowed to watch over their actions in death, always illuminated by the soft glow of the fireflies. Through this, much is revealed about the end of their innocence, their struggle to survive, and their search for joy and happiness, and it's said without any words. The narrator seldom appears after the beginning, saying only a few choice objective facts. When he comes on again at the very end of the movie, finally we see everything come to a quick and merciless end, set to a somber tune by Michio Mamiya. We leave the world of the living and join Seita and Setsuko in death once again, as they speak affectionately and softly, holding the tin of their innocence and surrounded by fireflies. As Setsuko goes to sleep, the shot of Tokyo appears before the movie fades and the credits roll. It's the emotional climax that we were never afforded in their lives, and as if to hit us all at once, the somber images from earlier in the movie—from the death of their mother to Setsuko playing by their shelter—finally come together, and allow us to experience more sadness than any child should ever see. It's heartbreaking in a way that few works ever approach.

Grave of the Fireflies hit me deeply. If I sound preachy, it's simply because I have never had an experience like Grave of the Fireflies , and every time I watch it something new appears. I am a cold heartless bastard who laughs when the main characters die in movies, and I could not stop crying in the final scenes. The bittersweet ending—and yes, I disagree with people who would claim it's plain sad—hit me more than any anime or drama, and in a more profoundly human way than any live action movie I have seen.

Which brings us to an interesting point about it: why was it chosen as an anime film rather than a live action? Ghibli shows us time and time again how anime can be used to provide fantastical images of wonder that go beyond anything live actors could render. But this work has none of that; quite the opposite, the images would have been much grittier and harsher if there was no animation involved. After having rewatched it a number of times, I realized that harsh images of the war were unnecessary. The movie follows Seita and Setsuko, and so we should take the events on screen as their perspective. And in that regard, the softer tones of animation provide an innocent quality to everything, which creates a stark contrast in the tougher images such as the mother’s burnt body. With a lighter color palate and painted effect, those shots appear as confusing, even fake, as if the mother is acting. It feels as if the children are flowering this image rather than internalizing it. And when night falls and the children are surrounded by fireflies, there is a sense of wonder and beauty that rivals Ghibli’s fantasies, even ones as enthralling as Spirited Away. Cut to the next morning, with its usual lighter palate, as Setsuko buries the fireflies in a mass grave, as she imagines their mother was. The jarring change is so human, and yet the animation allows us to experience both emotions in sequence, affording them a dreamlike quality that almost allows us to escape the truth of it all.

I mentioned the notion of blame earlier. The film does not blame the Americans, who bomb Tokyo and kill countless people, including Seita and Setsuko’s mother. It does not blame the Japanese, who are too busy surviving and aiding the war effort to treat each other with basic human decency. It does not blame Seita, who steals food during wartime and yet has too much pride to save Setsuko in the end. Everyone shares in the fault because of their basic flaws as people, and so rather than blame any of them, Grave of the Fireflies blames the war for forcing these terrible conflicts out of people, and offers a reminder to the viewers about the conflicts that they had to go through. It reminds people that there is too much happiness in the world to warrant fighting, paradoxically by showing Seita and Setsuko finding small moments of happiness amidst all the terror, and choosing life in the face of relentless death simply because they can still find things to love about it. It reminds people that it's always the right time to treasure one another, to treasure life. All this paints it as a sad film, which is not inaccurate by any stretch of the imagination. The name Grave of the Fireflies solidifies death as the prominent image of the film. But the narrative plays out like a firefly’s life, and so with the inevitable death cutting their lives short, there is a brief and touching beauty that gives their futile struggle meaning.