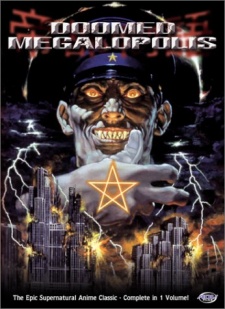

A number of external factors came together for the anarchistic ghost story Doomed Megalopolis to come together. Madhouse was one of the studios at the center of the OVA epidemic of the late 80's and early 90's, putting out dozens of supernatural works, and here we see plenty of names tied to those cult classics, with producer Maruyama Masao and directors Rintarou and Katayama Katzuyoshi took the helm. Their work on these sorts of stories was easily the biggest oeurve in the business by 1991, from Take the X Train to Demon City Shinjuku and beyond. It also rode that wave of interest from the late 80's of course, but one has to appreciate Doomed Megalopolis' timing in particular; closing out the year where Japan's 40 year postwar economy crashed with a story of a sorcerer in a World War II military uniform razing Tokyo might be a little too close for comfort.

The biggest difference I found between Doomed Megalopolis and similar works from the time is how that sorcerer, Katou Masanori, is the sole antagonist. Besides the supernatural forces he awakens beneath Tokyo, every assault on the onmyouji defending the city is led by Masanori himself, and we get no other high-profile enemies. He appears everywhere and anywhere, in spirit or in flesh, with a seemingly limitless pool of power and skill. He fights with hordes of shikigami, or with his own crushing strength, and sometimes he just lures people into hell.

The main targets for that last technique are the women. The fighters contracted to resist Masanori are all men, and professionals at that, but the actual conflict hinges around a trio of spiritual women—Yukari, her daughter Yukiko, and the shrine maiden Keiko—all of whom face different seductions by Masanori. The first two episodes take this to an unhealthy level, with phallic monsters bursting from Yukari's mouth right after Masanori calls her “his woman”, or his repeated attempts at raping both her and her daughter Yukiko in a world that couldn't really be described as completely physical nor completely mental. Even some of the men opposing Masanori get in on the action, with Keiko being suppressed by her husband for “acting out” and the repeated appearance of an incest plot (not to imply mutual consent) with Yukari's brother. This sort of story from Rintarou is nowhere near unprecedented, but I was close to dropping it altogether.

But while the more sensitive horror elements of the early episodes give way to more bombastic and large-scale fights, those creepier parts also straighten out somewhat in the second half. Keiko's strong personality persists against her husband's wishes, leading her to be perhaps the only spiritualist in the show that can genuinely resist Masanori's head-on assaults. Yukiko is younger and more passive than Yukari, but through her Keiko finds the way to end the conflict, which involves a boddhisatva whose origins are just as old, if not older, than the onmyoudo that Masanori and the others follow. We see her clothes completely stripped off, yet the camerawork manages to dodge the sensual angles it stressed before and gives her a firm position of power.

Of course the actual details of the story are a fair bit more complicated than I'm making them out to be. Fans of Japanese occult and ceremony will find many rituals straight from the works of Abe no Senmei and other historical onmyouji, as well as a deft weaving of different belief systems. The forces that Masanori seeks to disturb come from onmyoudo, samurai culture, and Feng Shui, while the resistance is an amalgam of onmyoudo and Shinto, complete with a robot suicide bomber. The granier cel style of the 90's creates heavy contrast between their powers and the background lighting, whether it be intense glare or cutting through hazy black backgrounds. The scenes of destruction by Masanori are gripping and would've fit right in with a fully realistic historical recounting of the Great Kanto earthquake and its aftermath. The central story of Masanori seeking to ruin Tokyo is a constant, but with him as a ubiquitous figure the otherwise simple plot maintains a pretty extensive network of factions and characters. If I can steel myself for the creepy scenes of the first two episodes I may want to go back and follow all the threads more carefully, as it's certainly a story that made me feel like I missed a lot.

The timing covers the Taisho period almost exactly, only a few extra years on either end, meaning that all the fictional events are tied to the rapid upheaval of the 1910's and 20's, from the death of the Emperors Meiji and Hirai to the Great Kanto earthquake. Beyond just wearing a Japanese military outfit, Katou Masanori is an onmyouji, one of Japan's ancient shaman-sorcerers from the Heian era. His goal is resurrecting Taira no Masakado, a legendary samurai in Japanese history who led one of history's largest insurrections against the government before being killed by his cousin out of revenge. Everything about Masanori and the time period for Doomed Megalopolis is steeped in Japan's history, Japanese resentment and frustrations, famous tales of Japanese exceptionalism crushed in order to reach the current era. And his goal is to destroy the shining light of Japanese exceptionalism of today, to bring down Tokyo and all its inhabitants. It must've been a terrifying thought for the people reading Hiroshi Aramata's original Teito Monogatari novel in 1983, alongside Japan's apocalyptic science fiction and Grave of the Fireflies' unsettling final shots of Tokyo framed by the dead, but while the economy only got bigger in the 8 years it took to adapt Teito Monogatari, they certainly picked the perfect time to release it.