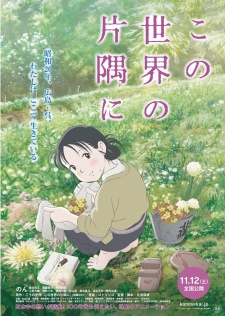

Anime has proven time and time again that when it comes to war, and particularly World War II, some of the greatest stories happen on the smallest scale. I say greatest and not grandest, because for as horrific as the imagery of the front lines has been since Fires on the Plain and even before, the stories of Grave of the Fireflies, Barefoot Gen, and Kayoko's Diary are not just disturbing and hopeless, but also force us to realize the ubiquitous nature of war, how it reaches well beyond the battlefield and into people's homes. These are the films that to me come closest to refuting Francois Truffant's legendary sentiment that there's no such thing as an anti-war film, because of how by being titillating it defeats its own purpose. These films couldn't very well be considered titilating, least of all In This Corner of the World, which inherited both the artistry of its director Katabuchi Sunao, the poetry of author Kouno Fumiyo, and of course the power and darkness of all the great World War II civilian dramas that came before it.

The film stands out immediately for the way it flows, which I can best describe using the Japanese sentiment of “mono no aware”, or “things as they are.” The story of Urano Suzu's childhood in Hiroshima, and subsequently her time as a housewife in the neighboring town of Kure, is both a coherent and continuous narrative and yet told through short scenes that are strung together like vignettes. The structure of these stories is similar to a 4-koma manga with setups, punchlines, and immediately a cut away from the scene, but it's clear that we're watching her life as she changes, grows, and learns, so we can't write these stories off as an aimless peek into her life rather than a fully-fledged coming of age story. Not to mention that as time passes and the war progresses, the humorous punch lines come fewer and farther between, giving way to tragedy and deliberations on how best to move forward. This sort of tonal shift isn't unheard of by any stretch—all three of the predecessor films I mentioned in the introduction follow children through much the same downwards spiral—but the fragmentation of stories prevents us from having a unbroken time of mourning, and instead forcing us to see the immediate consequences. It's forcing us to see things as they are.

And the experience of how things are is almost always a purely objective one. The pastel color palate and rough outlines gives the Japan of In This Corner of the World a dreamlike quality, but the background music often falls silent, forcing us to see exactly what's occurring on screen, a combination we saw in last year's Grimgar of Fantasy and Ash. Where this changes is in the scenes that shock Suzu's worldview, such as the quiet lake in the woods where she first fell in love, the view of Kure's fire bombing from atop her mountainside garden, or the spontaneous detonation of a burrowed missile on the street. Here we see the mind of the artist Suzu come to life, envisioning the world as a virulent watercolor, or the sky as a canvas being painted across in realtime, and most shockingly a single yellow line across a screen of black. These are the shots, I suspect, that won it the Oofuji Noburo prize when the committee consciously tries to avoid giving the award to feature-length films by major studios such as MAPPA. Despite those origins, the subversion of objectivity with these beautiful artistic moments was something we see much more of from the indie scene, from shorts like the Geidai Animation and Kyoto Seika graduation projects, than from established studios.

There are so many other aspects of the design that construct the mood, to the extent that it's frankly hard to fully assess how this style impacts the experience of the narrative. One complaint about this type of story, involving the firebombing of civilian cities and the atomic bomb, is that they have a nationalist bend that unilaterally criticizes the “enemy,” thus praising Japan by omission. Of course for the best works like Grave of the Fireflies this couldn't be less true, and I would say it doesn't hold for In This Corner of the World either, but the design does reflect a traditional Japanese mentality. The men are posed stoutly, straight from head to toe, and the women have a heavy back-and-forth curvature to their posture that reminds me of early Meiji ukiyo-e prints, though the everyday western clothes make it slightly less seductive than those courtesan prints. Shots are frequently set on a bridge, a setting we see a lot of in block prints from the same time, or atop a hill looking down over Kure, hemmed in by mountains on all sides and the ocean in the back, a spacious but sheltered world.

I realize I've said very little about the actual content of the film up to this point, but part of the appeal in making this movie is that Suzu's experience could've been the same as anyone else's. She has her personality quirks, being clumsy yet artistic, honest in voicing her thoughts but rarely if ever angry, and trying to find the best way to live her life in her new town of Kure, being wedded off at eighteen to a boy she met once on a bridge over a decade before. Her character is amusing but straightforward in the first half, suitable for the quiet vignette comedy as we build up to the last year of the war. But as she experiences tragedy she realizes that love and hard work aren't enough to prevent tragedy, which sometimes comes as pure chance or coincidence. We see her reject her new home, and then after a deliberation go back to save it even at the risk of her own life. We see her get sick and delay her trip home for a week, saving herself from the bomb in the process, which they barely notice as a flash in their town. And as we see the other townspeople fighting to stave off homelessness and starvation, there's a sense that any of them would have a similar story to tell, coming to Kure for whatever reason and finding themselves supporting their country and their family in any way they can.

So instead of talking about plot or specific characters, I spend most of my time on the atmosphere In This Corner of the World evokes, and note that the salient aspects of the plot and characters only elevate that atmosphere to a higher level of mastery. Five days after seeing the film in proper I find myself mostly thinking back to images, and to some of the lines that most captured the bitter cruelty of their lives as the war comes to a close. The one that echoed the most with me was the scene of Japan's surrender. In an uncharacteristic frustration and sanguine rage, Suzu laments that the country couldn't fight to the last man as the emperor had originally promised, and laments the fact that she didn't die as a daydreamer. For every canned or forced line in the early part of the film, there was one in the latter half that shook my concept of the characters, but moreso shook my view of how people are shaped by the needs and whims of war. I do genuinely feel like there's not a moment or image in the film that could be taken to represent an argument for Truffant; rather the film takes Suzu as a frame to argue for how war leaves dreams unrealized, keeps the bodies off the screen but the memories of their life vivid and raw, and slowly takes away the joys of life. It's only after that surrender, that brutal trauma left in Suzu's mind, that they begin to heal and to hope.