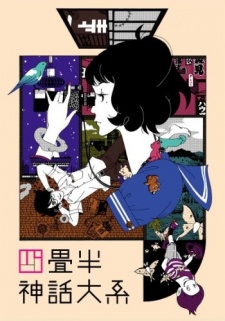

One of the last episodes of The Tatami Galaxy begins with our nameless protagonist reveling in the virtues of the 4.5 tatami mat room. It is a perfect square with enough size to live comfortably in, and yet not unreasonably large or wasteful. He has spent the first two golden years of his college career cooped up in the room he idolizes so much, doing nothing but making it into the next day while touting it as the pinnacle of his ideals. The 4.5 tatami room is the only thing in the world that can be considered perfect; clubs and people are greatly flawed, and the mythical treasure that is the rose-colored campus life is but a dream for those without his sense of aesthetics and foresight into the nature of the world. Describing himself as a recognized authority of the 4.5 tatami room, he declares that it is the perfect size for humanity to rule over, and asserts that the 4.5 tatami room is his entire world.

From these two ideas, laid back to back, an uncomfortable feeling permeates through our minds. It's clear that the room is the one controlling him. The Tatami Galaxy is laid out in a series of lives our protagonist goes through, seeking the mythical rose-colored campus life, and the raven-haired beauties that await him at its pinnacle. Every time he joins a new club, he is quickly relegated to the fringes of their society. But it is from these fringes that he inevitably meets the same friends, and quickly passes through two years of absurdity in their presence. He moves nowhere in the club. That's irrelevant to us, as he's clearly having fun, but it's all that is relevant to him. At the end of it all our protagonist wishes to go back to that fateful beginning, where he chose the wrong door on his quest to find his ultimate life. The clock tower, looming over the campus, faithfully stops and rewinds, allowing him to try again, to choose a new door, and to ultimately go through a different process to the exact same end.

What an unfortunate human being he is. He is inevitably trapped in a friendship with his classmate Ozu, a man of lies, slander, and not a shred of conscience, who devotes all his energies to making sure our protagonist makes nothing of his life. The one girl our protagonist can even enjoy his time with is not a raven-haired beauty, but rather an engineering underclassman named Akashi, a girl with a cold disposition to everyone around her, firmly isolating her from the rest of society. He meets a dentist, an eighth year bum, a breast fanatic, a love doll, and many others who lead him astray. He lacks the body for an athletic club and the popularity for a social circle, and by the time he realizes any of this, his chance to make a place for himself in the world has passed him by. He truly can do no right in his lives.

He also never leaves the center spotlight of our show, narrating every thought that passes through his logical brain, speaking in a form of Japanese reserved for essays and research at a breakneck pace while still maintaining a complete monotone. His internal monologues are the most perfect representation of the mind of a college student that has ever been written, speaking in roundabout ways that serve to disguise his true thoughts even from himself, all the while appearing logical and thoughtful. His analogies and rants are absolutely hilarious, as if to serve as his sole form of entertainment in life.

When he interacts with the equally comical Ozu, the line between his spoken words and his unspoken words becomes blurred to the point of undecipherability, and yet whether he speaks his lines or simply thinks them, Ozu understands him loud and clear. Ozu perverts the Japanese ideal of the red thread of fate that connects lovers, and claims that he and the protagonist are connected by the black thread of fate that draws them together with certainty so that they can ruin each other’s lives. It later becomes clear that the black thread of fate is the black thread of friendship, connecting together two people with the potential to superbly waste time turning each other into the scum of society with zeal.

A stronger way to get a grasp on the protagonist’s true feelings are by director Yuasa Masaaki's exceptional use of color in the world, which often hijack images of reality to turn them into monotone representations of his interpretation of what is truly happening. Color projects all the emotions in The Tatami Galaxy, along with a scarce few tracks of background music that rarely do more than subtly underscore the events on screen in comical ways. The animation itself, like the color, serves far less to show reality than to emphasize a particular circumstance. Often, real images of Kyoto are run through the show’s color palate to give us a moment to breathe from outside the action of the show, and to just take in the natural beauty of the expansive city he lives in. Having lived in Kyoto for two months at the time of writing this review, these shots struck a chord with me, as it really made it feel like these characters were living and breathing on the screen, enjoying the Kawaramachi shopping district, fishing by the Kamogawa delta, watching the Gozan festival from the Kamo-oohashi as the shallow river runs below.

An example is the best way to illustrate. In a drinking contest between the protagonist and a man trying to show off his macho qualities, the setting starts with the design of a high-end restaurant, with plain brown walls, a brightly-colored table, and a nightscape out the window. The lines are all fairly straight and physically feasible. As they both take the first drink, a giant lump representing the wine travels from their head to their stomachs before disappearing. Their faces suddenly turn bright red as the drink goes down. Drink after drink their dialogue becomes more nonsensical, their voices slurred, their designs more scribbled and childish. Soon the screen splits to show the two of them drinking, then splits again to show them both drinking twice, then four times, and the screen keeps dividing vertically until they become slivers of animation, bulging as the wine goes down. All the while a quiet but comical clarinet track plays. Suddenly, the other man snaps his fingers and all the colors invert as he proposes in a squeaky voice that they move on to Johnny Walker, colored neon green. When the battle finally ends, the loser collapses on the ground, and the scene rewinds by a few seconds just to watch him fall again.

Why do I insist on going to such lengths to describe the visual style? Because it is more inventive and rich than almost any other anime I have ever watched, and while it veers from the traditional style of objectively portraying the events on camera, it paradoxically feels more akin to how we would see the world as the narrator. And besides being inventive, it is also just so much damn fun. I loved every second of the show even putting aside the plot and dialogues.

How could we be having so much fun, but the protagonist is so depressed with the life he obtained that he asks to do it all over, time after time after time? All the characters around him receive rich characterization, but the fun of the show is finding those traits for yourself, incrementally through each of the lives our protagonist leads. As we learn more about them, their designs and lines change ever so slightly, so that even when they go through the same seemingly one-dimensional actions in any given world, we are drawn to the details in them that our protagonist could not possibly understand from the singular position he occupies. When the show was over I left my room and went down to the Kamo-oohashi, a part of me sincerely hoping that Ozu or Akashi would pass me by.

And yet as was said at the outset of this review, our protagonist chooses to devote his life to the 4.5 tatami room, portrayed with straight lines, real-life images, and a natural coloring, always shown in a true square to convey its perfect aesthetic. In each world he goes through during the early stages of the show, the room obtains something slightly different, whether it be a backpack of 1000 yen bills in the corner, boxes upon boxes of jelly, or even a neon sign from a Chinese restaurant. There is always a little white plushy hanging from a string attached to the room lamp. Every day he grabs that plushy to turn the light off before bed. It did not have to be there, and really it is only there by random chance. Akashi owns a set of five that are a way for her to relax when she encounters moths, which she has strong distaste for. One of them becomes lost in the most mysterious of ways, and the protagonist finds it and takes it home, vowing to return it to her. Every single world has this incredibly improbably event occur, and yet as he squeezes it to turn off the light every night he never finds a way to return it. He inevitably lets the chance pass him by, guaranteed.

For a seemingly fruitless and wasted life, he has so many opportunities dangling in front of him that he misses constantly. The promise to return Akashi’s plushy is accompanied with a promise to Akashi that would allow them to meet again, be it to go eat ramen together or to watch his latest homemade film, and yet he fails to fulfill these promises too. Upstairs lives an eighth year student who surrounds himself by useless pleasures and people, leading the kind of lifestyle that our protagonist despises. Up there, everyone our protagonist meets is busy having fun and wasting their college life, and while he tries to fit in in one world, he ends up looking back on his two years with them as useless. After every chance to play and waste his time drinking with the mysterious man upstairs, indulging in Ozu’s absurdity, and a chance at romance with Akashi simply by pulling the literal red thread attached to the plushy, he still choses the empty and perfect solace of his room in the end.

The result is a last metaphysical journey into the nature of youth, his life, and true happiness. He wastes two years of his life cooped up in his room doing absolutely nothing, and yet in a trick of fate he grabs hold of his ideal future. The Tatami Galaxy’s fantasy elements are a thin layer on top of the reality of a college student’s existence, designed to bring out the inner turmoil he faces going through life in a tangible and meaningful way. All the repetitions we have gone through that have their own quirks and insights come together in what is nothing short of a masterful ending, weaving together for our protagonist the truths that we have slowly pieced together after so much time spent getting to know the characters, getting to know them as friends we wish we could have, as friends our protagonist wishes he could find from the lonely confines of his perfect 4.5 tatami room.

Many shows have reaffirmed my belief that the medium of anime is a strong and lush way to tell stories and discuss truths about the world. Only a select few have made me reconsider what I feel the nature of anime and animation to be. The Tatami Galaxy stands as the only work of any medium to make me reconsider what I consider my life to be. In choosing a specific college setting, specific clubs, specific characters with specific traits, and a very specific narrative style, it transcends its setting, its characters, and even its medium, and it speaks to us with a profundity that I would not have believed possible for someone who has not gone through the endless repeating hell of our protagonist. And yet there it is, left for us to discover through our own lens as an audience and a person living out their own lives in the way we feel is best. If you are lost in life, watch it. If you know how to move forward but are still frozen in place, watch it. If you have a life to be proud of but doubt that it is truly the best place for you to be, watch it. To me the paradoxical message of The Tatami Galaxy is that there is always more we could do to be enjoying our lives, and yet there is no way to have a life more worth enjoying.