A pair of hands hangs in front of the screen, white and pure like a baby’s in contrast to the pitch black background. As they rotate and dance with one another, the left hand disappears and the right becomes flushed with a dilapidated brown tinge, standing in pure stillness and absolute silence for just a brief moment before the fingers move towards the palm and the knuckles crack in disunion. Suddenly after a fade to black, a frenetic chorus of violins heralds the sudden appearance of a translucent blue egg with a disproportioned bird fetus inside, suspended in the air by white tendrils in front of an endless storm that gently moves towards the screen. The scenes have no connection, nor do either of them connect directly to the greater work at large, but between the tensing of the hand and the appearance of the titular angel’s egg we are left with the nauseating suspicion that the egg has been cracked, that innocence has led to disillusionment and that the pure-white egg we will later see pervading throughout Oshii Mamoru’s haunting film Angel’s Egg belies a visceral ugliness within, and a coming danger without.

It could be said that the entire work is constructed of shots like these. There are less than thirty lines of dialogue throughout the movie, but the video and soundtrack fill the void so expressively words would have felt like a burden. After two opening shots framed in a warm glowing red, the palate shifts into a dark stormy blue with subdued whites and pervasive blacks. Those opening shots are taken from so far away that the world is made to look vast, expansive, too large to possibly explore. When the film begins in earnest, we enter a city so lifeless, so empty of any presence that we cannot be helped but for thinking it is hell, and in the camera shots kept so close to the ground we can never get a grasp on how far it truly goes, or if there is even a world outside. These two different approaches both serve to make the world feel terrifyingly wide, and so in the narrow corridors of the hellish city’s streets illuminated by a dark blue glow we begin to feel safe, hidden from the world at large.

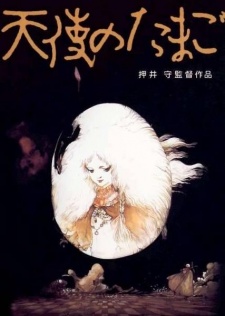

The one presence that illuminates those streets is the girl. She wakes up in a broken tower above the city with an egg in her bed, which she ignores in the red shot overlooking the city but is subsequently shown to hold it tight, underneath her clothing right above her heart. She walks aimlessly throughout the city, picking up spherical bottles of water and drinking them down. Is it from necessity, or is this an occupation she chose on a whim? We later see a room lined with the bottles and it is implied that each one represents a day she has been in the city. Not seeing the extent of them for ourselves, we assume that she has been here forever, possibly even since the city was borne into existence. Her flowing white hair causes her surroundings to be illuminated, and while that could perhaps only be a necessity of animating her small figure against a darker backdrop it also affords her a brilliant presence, lending herself to being the mysterious angel of the title also given that she holds the egg so close. Her red clothing also stands in contrast to the city, perhaps hearkening to the warmer world we see flash so briefly before the opening credits.

The other character is the man, rugged and dark-skinned but a mane of white hair himself, dressed in a blue cloak and carrying an intricately malformed cross of bronze. Perhaps this is where Oshii places himself within his work, famous for centering his films on his own personal musings and experience. The man, who stands in such high contrast to the initial sunset and checkerboard floor he stands on, eventually reappears in the city in front of the girl, and here he perfectly blends in to the blue backdrop save for two things: his white hair and the red jewel at the center of his cross. His elder age and solid unmoving features put him more at home in the city than the girl, and yet he is clearly trespassing in her space; when he moves towards her, she wordlessly contorts in fear before running throughout the city’s nooks and crannies she seems to have internalized like her own palm. However, in a passing shot we see her walk from an alley shaded in complete darkness, then looking back and walking slowly back towards it until the man appears directly in front of her, spawning from the shadows of the alley itself.

But as time goes on, she naturally closes the distance between them and they wander together, ending up at her home where a diagram of a tree stands. He sits and stares at it longingly, lost in thought, before launching into a darker twist on the biblical story of the flood, stopping the story after the dove flies away as if he were still waiting for it to come back. Here we see him lost, alienated and longing for a sign to validate his endless anguished wait. The girl, comfortable in her own home, takes him by the hand and leads him to the dove he was looking for, up in the attic. And yet perhaps we even know what is to be revealed of the bird but a second later, skeletal and inlaid with the wall as if it had been there for millions of years. The egg, she then finally reveals, is her attempt to bring another one back. She at him and then at the skeleton with a nurturing gaze, while he stares at the skeleton on the verge of tears. They exchange words and are looking at the same place, but in that instant we feel that their worlds that had begun to converge become ripped apart.

After the skeleton is revealed in parallel to the fetus we saw at the very beginning, the scene ends and the girl is shown sleeping in the bed she woke up on when she found the egg, two bookends placed together, but just as the skeleton is dead, the man has given up hope on the egg and his salvation, and after a three minute still of a fire smoldering out as she sleeps he takes his cross and holds it above the egg, as if ready to smash it in two. Knowing that this movie was possibly conceived of as a representation of Oshii’s fall from grace, we feel viscerally his emotions smoldering during those three minutes, and perhaps maybe even sympathize with him past this act of supreme cruelty he is inflicting on the girl who innocently holds him close for safety. That he does it with his own tired cross, which he would continue to hold even as the movie draws to a close a few shots later, is straightforward almost to the point of incongruence given the intense subtlety of the rest of the work.

The brilliance of Angel’s Egg lies with all of these symbols, all of these modes of contrast and progression that can direct our feelings on a whim without any exchange of words, with subdued visuals and a meandering if not nonexistent sense of pacing and plot progression. It lies in being underscored by a soundtrack of wailing voices and soft but assertive piano, and in the intense detail with which this rich environment is rendered down to every last broken cobblestone or dangling wire.

If it all seems heavy handed, then it is worth noting that the various details often stand in contrast to one another, resisting being reduced to any straightforward interpretation. For example, following the convention of darkness and blues as the feminine yin and the girl’s presence within the city as a home, we would consider this entire world a feminine space intruded upon by the masculine other, his very arrival heralded by a sudden and jarring procession of red tanks with phallic gun barrels. And yet she wears red, both traditionally masculine and at odds with the rest of the embryotic space surrounding her, while he wears blue and ultimately shows the first signs of sadness and true emotional vulnerability at the sight of the bird.

Another example is the way in which having broken the egg, he stands alone on a beach as the camera pans out for five whole minutes to reveal the absolute minuteness of the world of Angel’s Egg, set in a much vaster space. He stands alone on that beach as the ship he sees set against the red sun in his opening appearance departs from the world, unmoving as the camera leaves him behind, leaving him with no escape from this hell he has gone through, and we are left to wonder why he decided to smash the egg knowing that he alienates himself from his one presence in this dead world.

Just before this scene we see the girl falling into a ravine in anguish, falling after chasing his last vestige from behind. In contrast to the image of the fall, we see her reflection in the water, pale and ghostly, falling upwards to meet her. Here is the true image of water in the film, after endless rain in the city and her collecting water bottles day after day to sustain her life, after the terror of shadowy fish swimming across the streets and walls presented the shadow of an apocalypse long since past; despite all this the true water that swallows her up is the quiet stream lying at the bottom of the cliff. As she finally meets her twin, a disturbing shot occurs: the reflection is the one that penetrates through, her true form dispersing as if it were only an image on the surface of the stream. It is just before this shot that the camera switches sides, from following her descent to watching her fall towards us, changing our focus to the now physical entity that is her reflection. As the ripples dispel the brightly colored girl we know and we fall for a few seconds through the water with her ghostly counterpart, we are forced to consider our own position within this barren world. If it ends back with the man in the colored world left behind, are we being trapped along with Oshii within this illusionary hellscape? Who achieved salvation in the end, the man or the girl, both framed by the setting red sun so long ago? And where can we place ourselves to escape?