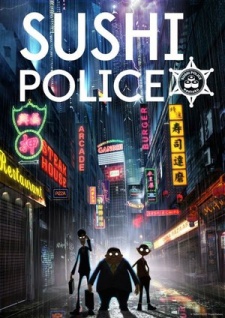

Sushi Police reads less like an anime and more like a colorful essay on the international politics of sushi in modern society. And so it bears mention that my instinct upon finishing the first few episodes was that the show barely passed for entertainment. From the opening scenes the 3D animation and overacted voices feel grating and out of place. But it's about sushi, a ubiquitously enjoyable topic, and it does promise a dramatization of Japan’s superiority complex towards their most popular food, told with robot chefs, guns that shoot wasabi, and the persecution of alligator, cream cheese, Nutella, and every other ingredient that should never have been allowed near raw fish and rice. And so I pressed on, and slowly the qualities that so annoyed me early on became a trademark, a way of further engaging this brilliant piece. In one of my most unexpected anime experiences to date, I started feverishly waiting each week for another episode to come out.

There is a lot of history and culture that needs to be covered in order to start looking closer at Sushi Police, so we start there. In what became a well-publicized event at the time, the agriculture minister of Japan in 2005, Matsuoka Toshikatsu, made a stop at a Japanese restaurant in Colorado during a business trip only to find sushi on the same menu as foreign cuisine. This event was symbolic of a much larger counter-culture movement in Japan, resisting the ways in which sushi had been perverted by other nations to bring it far outside the sphere of Japan’s traditional high cuisine. Thus the government tested out a system of sending undercover inspectors to review Japanese restaurants all over the world and give seals of “authenticity” only to establishments that served sushi in line with Japanese tradition. A wry commentary in the Washington Post responded by saying “So beware, America, home of the California roll. The Sushi Police are on their way.”

Sushi Police takes this to the extreme. Rather than rewarding proper establishments, the Sushi Police break into inauthentic sushi restaurants and put them out of business, firing gallons of wasabi and a space satellite soy sauce laser in the course of each of their raids. The team consists of Honda, a straight-edged man who listens for the wails of inauthentic sushi crying out in pain, his slightly bumbling assistant Suzuki, and their comic robot Kawasaki. Travelling in a literal flying ship—the kind normally meant for sailing—and taking on restaurants with names such as “Mr. Sushi Gillermo” and “Sushi Typhoon”, as well as a number of other shady foreign establishments, were the show not produced in Japan it would seem like an offensive parody.

The backlash to their violent oppression is swift. A movement called Free Sushi gains huge support following an American journalist named Sarah reporting on their numerous uses of excessive force, targeting even small-time family establishments and chefs who truly love sushi in their own way. As the Sushi Police receive missions that grow more and more extreme, they grow some doubts as to the morality of their actions. Honda barely waivers at all, obsessed with hearing the joyous calls of proper sushi happy to be eaten. Kawasaki on the other hand suffers from an internal programming conflict, attempting to resolve his purpose of making sushi for others to enjoy with his command to protect authentic sushi at all costs. Here we see one instance of Sushi Police’s satire: while Kawasaki is ordered to “protect authentic sushi”, Suzuki and Honda force him to interpret this as “destroy inauthentic sushi”. As the show progresses into its final stages, we see that these goals are not synonymous, but are actually discordant, with the latter being the root cause of sushi’s global decline.

While the show plays out in a straightforward manner from a plot perspective, every minor detail worked into the show is rife with meaning that complexifies the debate about sushi authentication. Note that Honda, who obsesses over the perfection of traditional sushi, is often shown drinking canned coffee, a product that was not only imported from Brazil but also comes in a metal package stored in a vending machine, a prospect that would make coffee lovers cry. Yet Japan adopted coffee long before it became a staple in Seattle and Europe, and even today they make it with an artistry and perfection that attracts customers worldwide. Why then is Honda, and by extension Japan, allowed to judge other countries for borrowing sushi and making it their own?

They also bring up the dirty secret of sushi: it originated as a Chinese method of storing fish for long periods of time, a process that rendered it sour and aged, exactly the opposite of their image of ideal sushi. Honda retaliates that China bore sushi, but Japan raised it, a response that doesn’t satiate Kawasaki just as it shouldn’t satiate us. Soon afterwards they go to destroy a factory line for mass-produced sushi, a clear admittance of Japan’s equal crime against sushi, with conveyer belt style sushi gaining mass popularity and robots being programmed to make perfect nigiri. For all they claim superiority, sushi came and left Japan in a form quite unlike their image.

There are more direct jabs taken at the Japanese government as well. Honda and Suzuki attempt to bribe Sarah, certainly one way for dealing with inconvenient press. A counterpoint to the Sushi Police, at one point we see the appearance of the Pasta Police, who are universally loved by restaurant-goers and who grant seals of authenticity even to hybrid restaurants serving pasta right alongside Japanese cuisine. To cultures outside of Japan, the importance is on making and enjoying a product worth making and enjoying, and while tradition is cherished, there are centuries of improvement and growth to work off of now.

In the hands of Sushi Police, even the technical aspects of the show are statements on Japan’s unfounded superiority complex. The headache-inducing art style is a reminder that anime itself was derived from foreign animation, and while it is certainly not up for debate that the foreign influence Japan brought to animation was a positive for the world, they haven’t adjusted to the modern world of 3D so pervasive in the West. The ending theme is a multicultural product, synthesizing Japan’s leading electronic group Perfume with the prolific new age American group Ok-Go, producing a song that is neither authentically American nor Japanese but is certainly enjoyable to both groups. Every episode ends with more objective historical and cultural facts about sushi, a way for viewers to become educated about sushi and thus have a more valid claim to participating in true sushi culture, regardless of more arbitrary factors such as nationality.

We see where it is indeed possible for the concept of sushi to be led astray. As addressed in a particularly bizarre episode involving company marketing a sushi teleporter, the transportation of sushi is a tricky debate, as raw fish easily becomes inedible and dangerous. Though there is nothing wrong with wanting to have access to one’s favorite cuisine even when it is too far to travel for, there are also health standards to be taken under consideration. Later on in the show we see Kawasaki make a perfect piece of sushi, so airtight that the rice cuts through wood. This is an example where the Japanese sense of space may hold sway; American sushi is typically made with much more pressure than the traditional version, but while it may sound silly to “pay hundreds of dollars for air,” the sushi is meant to be eaten, not for carpentry. And in a ridiculous failed science experiment, a growth ray meant to make this tiny inauspicious product more sizable and grand—clearly referencing the American standard of “bigger is better”—transforms a perfectly good tuna nigiri into the dreaded Sushilla, a Japanese kaiju monster that terrorizes New York. The irony of its forefather Godzilla being a stand-in for the horrors of nuclear power transfers over quite nicely to a statement on how some sushi is chemically abused.

We also see how sushi is loved by the new generation, in whatever perverse and warped form it may be in. Alongside the starry-eyed kids with their love of sushi are the older generation, who have no less love for their craft than the Japanese even if they may smother it in chili sauce. While it may be obvious to us that the Sushi Police are disliked for their actions, it turns out that by ruining inauthentic restaurants, they also create a decline in authentic sushi in the backlash. Everything ends on a positive note, reconciling the beauty of true authentic sushi with more modern and culturally diverse practices around the world. It may be a trite lesson to learn, but Sushi Police certainly sells it well: if the sushi is made with love and eaten with love, it has worth.