There was a clear moment in the first episode where I fell in love with Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinju. The nameless young man, fresh out of prison, is sent up to the stage. Nervous and shaking, yet cheerful as ever, he is ready to perform good rakugo. As he walks in with his practiced stride and fine kimono, he trips and the crowd laughs, but not unkindly. He sits down, and as he thanks the crowd for coming, he smacks his head against the floor, the microphone gently whining. As he prepares for his story he grins like a shark and launches right in. What we get from there on out is ten minutes of his performance, him altogether speaking three parts of dialogue as he weaves a humorous tale of an unlucky burglar and a conniving homeowner. We see what little we know of this man, reflected in his exaggerated yet controlled yelling, in his delivery that is nine parts practice, one part passion. I knew that it was good rakugo, not because the crowd is laughing occasionally nor because of any remarks from his master in the audience, but because for ten minutes I was absorbed in his story, laughing even before I heard the crowd reacting.

Here we learn the first unspoken rule of rakugo: the words are set in stone, but the rakugo belongs completely to the storyteller. Over the course of this thirteen-episode journey through the twentieth century, we watch the rise and fall of the classic Japanese art of comedy through the eyes of two young storytellers carrying the future of rakugo on their back. Sometimes we hear parts of the same story twice or even more, and yet we never hear the same rakugo twice. We hear sad rakugo, chilling rakugo, fast rakugo, good rakugo, bad rakugo; the story is secondary to the storyteller, a concept that is shown beautifully and never told.

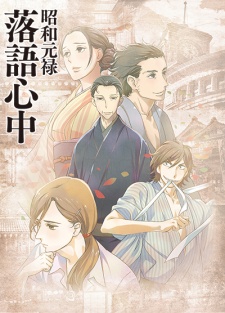

Naturally, the show itself borrows much of its structure from the art form. This scene from the first episode is not part of the central story, but rather a part of the preamble, setting the stage for the true Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinju. The man who tells the story at the beginning, contrary to our expectation, is not the central figure in this tale. The protagonist is his master Yakumo, formerly known as Kikuhiko, the last great storyteller of his era. Yakumo keeps the nameless man as his apprentice and houses another woman, the fierce-tempered Konatsu, with whom he shares a vitriolic hatred. He calls her an impudent child for wanting to practice rakugo, while she accuses him of killing her father, his fellow storyteller and lifelong friend Sukeroku. And soon, true to Yakumo’s role as a storyteller, he launches into the tale of his life with Sukeroku, stretching back to long before the second world war when the theaters were still packed every night.

Yakumo and Sukeroku arrive as nameless children at the house of the seventh generation Yuurakutei Yakumo to become his apprentices. One a pampered young boy cast out of his house after his burgeoning career as a dancer was cut short by a lifelong injury to his leg, while one a street brat with no parents but with a passion for rakugo. They instantly seem incompatible, but by the end of the first day, they open-up to one another.

We fast-forward to them leaving their master’s house to start their professional careers, after finally being given stage names to go by: Yakumo as Kikuhiko and Sukeroku as Hatsutarou. Kikuhiko studies and works all day, and while he would love to perform more, he ends up stuck in a slow and boring lifestyle, unable to truly express. Hatsutarou on the other hand is loud and boisterous, drawing large crowds every day to see his unrestrained style, only to go and spend all the money he made drinking. Kikuhiko resents Hatsutarou for being lazy, and most of all, for being so much more skilled. But Kikuhiko also loves him whenever he gets up on stage, a sentiment he never loses even as he finds his own voice.

Their personal differences are by no means a minor matter, for what is at stake in their upbringing is nothing less than the future of rakugo in Japan. Many of the older generation die over the course of the series. Even though the theaters that closed during the war open right back up after the surrender, there are few left to take on the mantle of rakugo in the postwar generation. Kikuhiko, a respectful and quiet man with spellbindingly classical performances, becomes the poster child for the older generation, but much to the ire of the elders, Hatsutarou is wild and disrespectful, telling stories as if he were in a movie or a theater. The two of them debate over their own future and the future of their dying art in a modern café, and we see them contrasted against live jazz and foreign liquors. It is a sign that the times are changing, and that these two are trapped in its center to either thrive or starve.

Further complicating their friendship and futures is the mysterious geisha Miyokichi, who comes back from Manchuria with her master and Hatsutarou. She takes a liking to the straight-laced Kikuhiko, tempting him away from a straightforward path, only later to suffer deeply in her own art. She is trapped in an outdated art, and yet she seeks out the company of a man whose life is defined by tradition and rigor. Her story is truly tragic, and while she appears little on screen she transcends from being a mere side character. Watching Miyokichi I was reminded of Kenji Mizoguchi’s classic The Life of Oharu—every time she appears desperate or resigned, she blames it on the men in her life, regardless of which man it was that made her suffer this time. This woman causes great stress between the two men; one leaves her for the sake of his own rakugo, and one would leave rakugo behind for her sake.

Names are used with deep symbolism in Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinju. We know that Kikuhiko must eventually inherit his master’s name and become the eighth generation Yakumo, while Hatsutarou pushes to take on the name of the deceased old man Sukeroku who trained him while he was still a brat on the streets. With one inheriting a name by succession as per tradition and the other taking a new name by choice, a clear split is seen in the 20th-century culture of rakugo. Also note: the men within the rakugo community are all nameless, while those who watch from the outside are not.

In fact, the emphasis on names gives rise to the two great climaxes of the show, even beyond the inevitable tragedy that ends Yakumo's tale. In the first, we learn Miyokichi's real name, a symbol of her humanity and of the humanity of the nameless man who calls it out in desperation. We were told right at the start what was about to come, but even then this revelation is overpowering, blindsiding, and cruel. The second is the exact opposite. In a brilliant shot towards the end, Kikuhiko, now the great eighth generation Yakumo, contemplates what would happen if he were to hang himself from a tree and leave the cruel world forever. But as he continues to speak under his breath, even that last desperate sentiment becomes a rakugo tale. He walks up onto the stage, head slumped forward, hands limped at his sides, going up the stairs into a blinding light as if he were walking to the gallows. As quick and unexpected as the end of any great rakugo story, even while reciting the story his mind speaks one last line: “My name is Yuurakutei Yakumo. I have long forgotten my real name”.

Thankfully the story is framed with hope. The titular word “Shinju” refers to the classic Japanese double-suicide plays. But when put into the title as Rakugo Shinju, it refers not to the deaths of Sukeroku and Miyokichi, but rather to rakugo and its last champion Yakumo, who even proclaims that it should it not be saved but should die (Shinju) with him. This isn’t the first time the Shinju motif has been used in anime to dwell on the concept of modernity (think back to a certain movie about fireflies). Yet, after the climactic scene above, we return to the present—ten years after he finished telling his epic tale—and rakugo is still alive. The nameless man who told that very first rakugo story we heard has carved his own niche in the world, and is ready to take a name worthy of his unbridled performing style. And just like that, the cycle continues with the old Yakumo and a new Sukeroku in the modern era. But that is rakugo: the words are always the same and the audience knows them by heart, but it is ultimately the storyteller who they have come to see, and with whom an old story becomes new.

Showa Genroku Rakugo Shinju is spellbinding. The irony of its existence is that it's marketed to the modern youth who know nothing of rakugo, arguing that it still has a place in modern society. Yet the work is an anime, the most pronounced example of a modern medium that has displaced traditional arts as the international cultural face of Japan. Nevertheless, this show doesn’t shy away from making us listen to good rakugo for ten straight minutes, convinced that its uninitiated audience will be enraptured by it all the same. Why wouldn't our attentions be captured when the show itself is an equal story worth telling? At times we laugh because of how unbridled and freely it moves. At times we sit still in anxiety and anticipation, waiting for its perfectly controlled performance to unfold. There are no cheap emotional thrills nor moments of pure drama played up with sweeping orchestral tracks—there are cobblestone streets and fireworks, jazz and dimly lit tatami-laid rooms. There are dozens of people whose lives are entangled with this delicate art, walking the line between performer and human. And at the center of it all are two men, profoundly complex and human, with centuries of tradition resting on their shoulders.