Ping Pong the Animation is about people who play ping pong first and about ping pong itself second. Few sports shows have put in as much research for the sake of rendering their sport in an intelligent, realistic, and technical light; in Ping Pong we get analysis on the types of rubber and blades used in real racquets, different grips that yield different playstyles, and a rendering of the actual matches that make them feel like a similar rally could take place in real life. But for all its technical prowess, Ping Pong is about people who play ping pong. I have never seen a show based on sports reach such a subtle and realistic level of character building. Every character, no matter how important or minor, feels like someone I could meet at a tournament, in a gym practicing all alone, in the bathroom before a game trying not to crack under the pressure. Their motivations are real, their fears are complex and grounded in the reality of competition, and of the network of teammates, rivals, and schools that have built them into the players we see them as on screen.

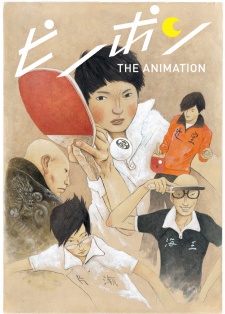

Ping Pong is about people who play ping pong, who love and give their lives to ping pong. It is about a boy who never smiles, and is thus nicknamed Smile by his peers, who treat him like an unfeeling machine as he surpasses all his peers while deflecting all personal feelings towards anything and anyone attached to the game. It is about his friend Peco, who takes a flippant arrogant attitude of infallibility towards the game until an exiled Chinese player nicknamed China exposes his skills as insufficient, and his devotion to the game as superficial. It is about Dragon, the fierce competitor with a firm hold on the world of high school ping pong and heir to a company devoted solely to the game. It is about a little boy trapped in a broom closet after school waiting for salvation. He chants three times: “Enter the hero. Enter the hero. Enter the hero.” And the hero appears from above to save him from despair.

The narrative of ping pong competitors, of students on the threshold of adult responsibilities, of people isolated geographically and physically and mentally, searching for a way out—the narrative is deftly crafted and interwoven, centered around the regional high school ping pong tournament that represents a test of their love and devotion to the game, as well as their skills and talent. Some have immeasurable potential but have lost their love for ping pong, and cruelly they steal the spotlight from those who love the game more than anything but have hit their limits. Smile begins as a strong player who can’t surpass his idol Peco, but China reveals both Peco’s weakness and Smile’s strength; he’s been losing on purpose to keep his friend happy. Peco leaves the world of ping pong, and Smile begins to lose his accommodating nature in favor of overwhelming skill. China, after losing in his home country and lowering himself to the inferior Japanese system to one day regain his former glory, loses to Dragon and finds himself at the limits of where he can reach alone. And at the end of the day, Dragon goes home to train ceaselessly, shutting out his lover and his family and his teammates to practice against a machine. Every time a competition comes around he disappears right before his match; we later see him alone in a bathroom stall, holding onto his sanity for dear life. Even the Dragon fears he will one day be left behind.

Any sport would have given an equally moving and stunning performance, but I think the choice of ping pong is particularly interesting because unlike the usual themes of sports and shounen anime, ping pong is a game where you compete alone. The different high schools may be “teams”, but we never see true camaraderie between members of the same school. Smile’s success forces everyone else in his school to be neglected and ultimately quit to get ahead in their looming post-graduation life, and Dragon pressures and berates his team for their lack of perfection; Peco and China are abandoned by their homes and are forced to fight on their own. Ironically, though Peco’s selfish attitude causes him to leave his high school team and China looks down upon the foreign Japanese amateurs, they are the ones who find camaraderie first, as they train with outside groups to improve their skills and are moved by the selfless way their peers devote their lives to becoming better at the game they love so much. When we see Smile and Dragon they are always alone, even in a crowd.

There are two distinct parallels to their story: that of their teachers, and that of the hero. Peco and Smile grew up playing in a local practice hall run by an old lady named Tamura who smokes and tries to discourage Peco’s nonsense. Their high school English teacher and ping pong coach takes an interest in Smile and starts training him specially. Later we learn from Tamura that he was once a skilled high schooler nicknamed Butterfly Joe for his floaty, darting play. He went soft on a friend who had an injury and lost a tournament match, never to make a showing on the ping pong scene again. We see him training Smile, desperately trying to impart some sense of his former self in the new rising star, while Tamura finally gets a chance to train an obedient Peco from the ground up, a chance to bring him up to be a better player than he ended up the first time in her care. The scene of the hero appears every so often, when Smile is isolated and humming, completely enveloped in his own mind. In these shots, we see Smile alone, but the boy in the closet is inevitably saved by the hero. Both of them are in the frame.

There are endless characters that stand out to me. One of the oldest students in Smile’s high school club is forced to give up his passion to run his parents’ hardware service. Dragon’s girlfriend—or at least we infer they are lovers, even though they never act like a couple—attempts to deal with her single-minded boyfriend and her role as a model for products for the very game that keeps Dragon away from her, even as we see his teammate obsessing over her in secret. A student named Egami appears as a random tournament opponent for Smile, who has little or no passion for ping pong and heads out to find his passion after he loses. He appears almost as an afterthought, but we see him appear a few times on the beach, in the mountains, and eventually in the stands of the next tournament. He sees everyone playing their heart out and he falls in love with the game all over again, crying into his newly tanned hands as he asks for forgiveness. It’s hard to be a bystander where you were once on the stage, but it’s also never too late to rediscover a passion.

The whole show is executed to a near flawless level, from an erratic hand-drawn style that has become the trademark of director Yuasa Masaaki to the use of an actual foreign voice actor for China, and of course the meticulous attention to detail with regards to ping pong itself. I have seen countless sports shows over the years, and there are patterns that tend to emerge, such as characters who specialize in specific moves and techniques like a shounen fighter and scenes of high tension with the opposing team that zeroes in on their respective group bonding. Upon closer inspection many of these tropes abstract the focus of the show away from the sport itself and onto the characters, but the characters are defined solely off of their love of the sport, and so the show cyclically fails to engage us with both the characters and the sport. Ping Pong has characters so well-characterized that they steal the spotlight from ping pong, but with the realism and detail with which the actual rallies are animated, the game also comes alive in its own right. Most importantly, success and failure is grounded in skill and training, meaning that pure emotion and plot can’t change the outcome of the game. Through this, victory and defeat gain meaning as the outcome of the characters actually playing ping pong, not the characters of a ping pong show having defined roles of protagonist and antagonist.

And ultimately there are no defined roles in Ping Pong. Smile is the main character, but as the focus shifts towards Peco one could even call Smile the antagonist, the one ultimately needing to change. China is a catalyst, but he is by no means left to the side as he is forced to grow and mature in his new home of Japan. As the age of Tamura and Butterfly Joe rose and fell, we are experiencing a transient period in ping pong history through its central players, and so aspects of morality are moot where seeing them as people come to the forefront. I said that ping pong is secondary, but it is through ping pong that we can see them as complex individuals, trying to decide their place in the world, and desperately holding on to the game.