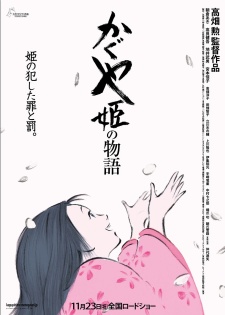

It only took me a moment to fall in love with Princess Kaguya. True to its roots as a traditional folktale, the movie opens on the title and runs through a series of static cards with the credits, set over a bright rice paper background with a soft, almost cold Joe Hisaishi track, blending the classic titular opening of pre-World War II films with even more ancient imagery, and evoking a sense of dignified incongruence that few but its acclaimed director Isao Takahata could do. While he has been a part of Studio Ghibli for decades, his animation style is instantly noticeable as distinctly non-Miyazaki-esque, as he chooses the palate and design to fit his ideal image of each specific movie. This time it was a beautiful hand drawn sketch style with a bright palate, which hits our eye as the narrator’s archaic storytelling Japanese hits our ear, and suddenly we are in a storybook world. A shot of a bamboo grove, the echo of distant knocks on a silent background, “Once upon a time, there lived a bamboo cutter”…and we drift.

Another hallmark of Takahata is his choice of material. Many have called Yasujiro Ozu the most Japanese of all directors, but no one in the medium of animation could possibly lay claim to the title over Takahata. “The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter”, on which Princess Kaguya is based, is Japan’s oldest narrative folktale, dating back to the 10th century, and in it are many formative details about Japan as a nation and as a culture. A bamboo cutter in the woods discovers a glowing bamboo shoot, where a tiny girl in imperial garb lays within, radiantly sitting in meditation. As he picks her up, she gives him a wide smile and falls asleep, and immediately he decides she is a gift from Heaven. He and his wife adopt the tiny child, and shortly thereafter it transforms into a baby, a baby who proceeds to age at an incredible rate, much in the way bamboo can grow a foot overnight. She is nicknamed “Lil’ Bamboo”, although her father never stops calling her “Princess”. Her formative days are learning and experiencing everything in her grasp, and in turn we get a series of hilarious and heartwarming images of her rolling around on the floor, chasing after bugs, tripping and spinning and crawling. I can only imagine how many hours the whole team spent observing babies act for those precious few moments.

As she grows older, making friends and intimately learning the forest around her, the bamboo cutter finds a trove of gold and robes in the bamboo grove, the tools to raise her to the status of a princess. They take her away one night to the capital city, where they begin a new life as royalty. The colors become more concrete, less dreamlike, and the music begins to feel more emotional than nostalgic. While she learns to live as a member of the aristocracy, she begins to struggle with her own sense of worth and identity. Her father makes all her decisions for her without discussion, at every step saying “How happy you will be now!” Her mother fashions a shed out in the back of the mansion and lives the humble life they once had, serving as a wise and loving emotional core for her. Soon she receives the name “Nayotake no Kaguya-hime”, which means “The Shining Princess of the Supple Bamboo”, and in a flash news of her beauty spreads throughout the capital. Five high ranking officials come to court her, but she cleverly turns them away when they compare her to various treasures of Chinese legend, asking them to bring her those very treasures. But at the same time, we see her turmoil as she is compared to things so radiant and irreplaceable, even when the five suitors have not seen her once. Where does her true value lie, if her beauty is being evaluated on hearsay alone?

The end of the film comes swiftly with Princess Kaguya’s summons to go back to her original home on the moon as she begins to find aspects of beauty in the world she had forsaken in her heart, longing to stay on earth for just a little longer. Those prayers go unanswered, and try as they might none of Kaguya’s horde of attendants can stop the moon folk from coming down and taking her away. They come on clouds in the form of boddhisatvas with a parade of heavenly music, and as she begs and pleads and resists, a robe slowly falls over her, and she goes silent in an instance. They depart, with her strict but adoring father and kind loving mother crying from the ground below. In these last moments, Takahata is truly heartless, giving us as little time to cry as her parents.

From here on out the original legend has tales of the emperor burning a letter to send it off to her, but it seems Takahata has chosen to spend every second he has on Kaguya herself, valuing the very human aspect of her growth and experience of the world over the later parts of the myth, which are valuable as a cultural record but not as a tale of the human experience. Kaguya is truly extraordinary, with a fickle mentality that is easily lifted or lowered by her immediate surroundings, but who we always trust to have a giant hearty laugh at the end of the day. Her singing, her playing, her anger and sadness, her curiosity, her love and happiness; all are projected beautifully, rendered in an acutely human way even through the hand sketched style. I remember every smile she ever made.

Yet while it has the potential to render beauty and soft emotions, Princess Kaguya also captures negative, confused emotion masterfully. The clear scene that sticks out is a sequence during the party celebrating her naming, where from the other room we hear a group of old men talking about how ugly she could possibly be, cajouling her father into bringing her out. At once Kaguya smashes the sea shell she is holding and runs out of the palanquin, through the sliding doors, through the mansion itself. The music quickens, the line get blurry and rough and black, until it looks like scribbles on the screen. She tears out of the mansion, and through the empty streets of the capital, leaving a trail of fine robes behind. The camera follows her initial dash, but as she leaves the city it freezes, bisecting her stream of dirt and the ominous moon above, with a dirty watercolor nightscape all around. The next shot cut images of her face contorted in pained fury with the unmoving moon above. By the end she has gone from being dressed like a doll to looking like a ratty beggar girl, all in the course of her dash. Like with the softer scenes, we see animation used in a way that is angry in a way that no live actors could ever fully render, breaking the boundaries of physics and indeed physical form. It's as if the animator Hashimoto Shinji was angry himself.

We get surprising emotion from side characters as well, and though their ultimate purpose is to make Kaguya’s experience of life concrete, we get a chance to peek into their lives as well. The strict father inadvertently pushed Kaguya away at every stage of her life, but in every decision he asserts “How happy you will be now!” with a beaming smile on his face. He is caught between loving her as a father and raising her to glory as a princess, and only at the end does he realize that he is allowed to forsake her birthright for their sake as a family. The mother reminds me of the strong, silent matriarch from Yasujiro Ozu’s masterpiece Tokyo Story, as a seemingly slow and frail woman with the intellect and emotional consistency needed to keep Kaguya sane and happy, to keep the family together. The five suitors have their quirks, the emperor’s naiveté about the lives of others comes out in just a few short scenes, and all the attendants within the mansion are at once archetypal and believable. There is one short attendant who looks like a personified cat, in all her mischievous ways, and Kaguya is rarely seen performing her aristocratic duties without her. She makes me laugh again and again and again, even with barely a few lines. She is another gift the animators gave us, something that clearly made every scene a joy to animate. Even she will get a chance to prove her desire for Kaguya’s happiness.

And so while all the traditional forms and morals about greed and family are ever-present in Takahata’s rendition, this version is clearly one of emotion, about rendering her life as it was to her rather than to us as a parable. After seeing both this and Grave of the Fireflies, Takahata’s other great masterpiece, I am convinced that he's unparalleled at the art of showing children playing, with the most minute attention to rendering even completely unnecessary little quirks for the sake of having us believe that these are real children, no matter how they may appear. Kaguya herself grows older but every so often we get a glimpse that she is really just a taller child, and every time she appears to have lost her innocence forever she comes back with a more serene, mature, and yet still distinctly childlike desire to play with the world as a whole. Every time she is dressed like a princess her face turns completely stoic, but clouded in a way that clearly hides her discontent. But as soon as the pomp and circumstance end, a mischievous smile plays across her face. She is curious about the world, as though it were completely foreign to her, and so when it comes time for her to be spirited away and she resists, it feels not like melodrama, but like the actual pangs of a child being ripped away from her playground and her parents, from familiarity, from happiness.

What we see is ancient Japan, no more and no less, but every bizarre archaic custom is an integral part of her life, and at its very core her life is one that could be lived in any age, in any country. In one fell swoop, Princess Kaguya captured feudal life and the stories of old, captured the warm feelings of growing up and experiencing life, captured the turmoil of feeling unwanted and worthless, of not belonging, captured the strength of animation as a storytelling medium, and from it’s very first moment, all the way through the final shots, it captured my heart.