When I sit down to write a review and my first instinct is to fill up the page with trigger warnings, things can only end well. On a related note, if you are triggered by death, rape, child exploitation, mental instability, genocide, torture, dehydration, starvation, depression, or have a tendency to get attached to your characters, I warn you now: Now and Then, Here and There does not mess around.

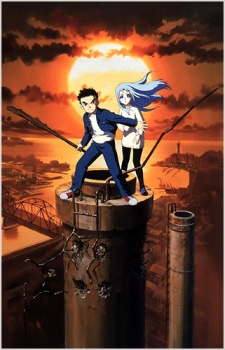

At the outset things are simple. A headstrong young boy nicknamed Shu goes through a normal day, losing a kendo match, not asking out the girl of his dreams, waving to all the people on the street, and enjoying a nice sunset from atop a smokestack in an abandoned construction site. There he meets Lala Ru, a quiet girl who is admiring the sunset from one of the other stacks, and before he can get more than a few words out of her an interdimensional rift opens and a wave of soldiers come to take her away. Where? Shu soon finds out, after trying to save her and getting pulled into the dimension from whence the soldiers came. The two of them keep fleeing through the massive ship they emerge onto, and for a while they escape, but soon Lala Ru is captured and Shu falls down a shaft leading to the outside. And for the last shot of the pilot, we finally get to see our new world.

It's terrifyingly breathtaking, even with the art of the day. The desolate desert wasteland illuminated by a deep red sunset matches the dull decayed exterior of the ship. The ship itself looks more like a tower, and soon we learn that it pretty much functions like one, being unable to move without water, its fuel. Water is absent in this world, and the directors made a good choice in making it the essential commodity. Without water, no one can live, but more important than the lives of all the soldiers is the ability of the ship to move. This is the view of the crazed king atop the tower, Hamdo. My first thought upon hearing his voice was the Joker. The voice had a madness that slowly grew and grew and grew until it snapped, bringing the speaker back to a monotone. Even the monotone was insane. Hamdo is written too well to be a typical mental ward-type character. He is babyish and fearful when threatened while defiant and narcissistic when given any vestige of control. It is a perfectly controlled performance, and it could hold the show up on its own.

Not that he goes unaccompanied. All the characters play their roles very well. Shu meets a girl named Sara shortly after coming to this world, who plays a conflicted mess of emotions being wrenched around by the cruelty of others. He meets the soldier Nabuca, who could be a typical rival character if it were not for Nabuca’s complete devotion to Hamdo. Many of the other soldiers also factor in, each holding their own unique traits that drive the show, but all of whom hold undying loyalty to Hamdo. In fact, seeing how the characters that have been pulled from their homes and had their lives traded for the disposable lot of a soldier, only to feel nothing but devotion, may have been more difficult to watch than the atrocities being committed across the board. Just as the show could have stood on Hamdo alone, it could have been fantastic in a completely different way if we never once met him. There are only a few characters for whom he does not represent some force of the world rather than a person.

And what he represents is war, conquering, atrocity, and decay. This show has some of the strongest anti-war statements in any anime of all time, despite there being a combined total of less than one episode with actual war. The fighting is between assassins and soldiers, or between soldiers who disagree, or simply over with a single shot. To those fighting, it is life and death; go one level up and it becomes a numbers game. Women and children do not escape either, as they function to grow the ranks of the king. The four women who appear prominently in this show are all very strong in their own way, but they also suffer the most of anyone at the hands of the war, even if not directly from the king. Most of the messages the show pushes border on overplayed, or too depressing. But in my opinion it skates that fine line, and skates it perfectly. The themes aren’t messages; they are visceral images and unfortunate characters. The only one it is worth hating is Hamdo, and he is not even sane enough to understand why.

Admittedly, Shu does not move far past his starting point. He does push the plot forward, but he feels inorganic in this world. This has potential as its own function; as we experience the world through his eyes, it feels even more menacing than if we were to take it from the perspective of someone who knows nothing else. But Shu feels a little too headstrong, upbeat, and unfazed by the circumstances. As a guess, if anyone else ended up in an alternate dimension—even if it looked twice as much like our own—it would be weeks before they could act normal again. Although for all the differences between the two worlds, it is fairly convenient that the universal language of all the characters, including the American, is Japanese, and that water, guns, clothing, gender, and almost everything else are in one-to-one correspondence with Japan. Except the food, they make a point of that being different.

For as big of a slip as this may seem, the world is immersive enough to leave this behind, and in truth, explaining it would have been a waste of episodes. Lala Ru has the power to summon water, but she gets weaker every time. Why? Why should we care? Once it sets up its own rules and boundaries, the show operates perfectly within them, and so it’s good enough for us as an audience to acclimate to them and enjoy the ride. Breaking the rules would be a different problem, but I for one am a huge supporter of allowing a framework to go unexplained. No plot points are introduced later based off rules pulled out of thin air for the sake of the plot. With 13 episodes, everything comes up front.

The artwork is old, but the atmosphere is perfect. The music is barely noticeable for the most part, but no corners were cut when it came to making the soundtrack fit the mood. The tropes of the age are still noticeable, particularly with a character like Shu leading the cast, and with stock character roles like the rival and the love interest seemingly along for the ride. But as mentioned earlier, no one else is as simple as they are laid out to be. Even more interesting is that few characters get the kind of backstory that would normally drive their development. Nabuca has a village to return to, and we see this constantly guiding his thoughts. But eventually “return home” was combined with “serve Hamdo to return home”, which yielded the singular thought “serve Hamdo”. Hamdo never gets a true backstory, and his assistant Abelia gets absolutely no exposition whatsoever. Strangely it doesn’t detract from their characters, and now that show after show has tried to pull exposition out of the stock book of plot devices and backstories, seeing characters with nothing but their circumstances propelling them forward is fine by me. It fits into the framework, and denying us that sort of information—the kind that none of the other characters are likely to have—gives it a more atmospheric sense of the danger they pose.

And for as much as I harp on Shu not growing, by the end of Now and Then, Here and There he gives off an air of having truly internalized all the terrible things he’s seen, and there are subtle ways in which he acts that show he has really grown. When he finally picks up the bag he dropped at the base of the smokestack at the very beginning of the show, he gives it a somber look, and for a character with as little thinking as him, this is a moment of reflection. It could have been a look of gratitude for escaping the terrible world of violence and human conflict, or for returning back to the familiar, forgiving world he has known all his life. The somber look gives him regret for everyone he leaves behind. He leaves behind all his friends who are still alive, never to see them again. For him the only difference between them and everyone who actually died is that he can have some hope that they will finally be happier.