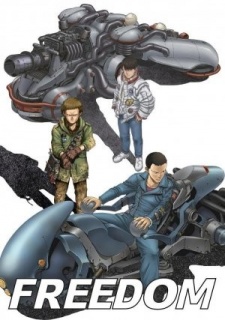

Nearly thirty years later and it’s clear that Akira still holds a special place in science fiction. Freedom , an adventure story of teenage adrenaline junkies caught between the gravity of their home on the moon and the call of exploring the long-lost Earth, is somewhat uncharacteristic of Studio Sunrise, missing all the mechs and political struggles they are known for through their seminal mecha work in the 80’s and even in more recent titles such as Code Geass, but even with a 3D style the characters are unmistakably that of Akira’s Otomo Katsuhiro, clear from the moment we meet them at the start of an Akira -esque motorcycle race. The world of underground motorcycle racing in the austere space colony of Eden has drawn together the hothead Takeru, the nervous engineer Bismark, and the calm rational Kazuma, in their quest to win and claw their way up the scene. This is not a story about their quest, just as Akira was never a story about motorcycle gangs. This is a story about their journey to Earth and back again.

A bust by the Eden authorities force Takeru and his friends into community service, where a set of coincidences and a photo of a girl on a beach lead them to discover that the Earth, long thought to be completely environmentally extinct, is as alive as ever. Clearly Eden knew the whole time, something we can glean by how the boys are immediately hunted by the government with only Takeru and Bismark making their escape aboard an old rusty space shuttle, but apparently they thought the government was chasing them down because they skipped work, and so once on Earth they set about trying to convince people to go up and visit Eden. Or maybe that’s just a side consequence of Takeru travelling across a somewhat deserted America just to find his new sweetheart Ao, the girl in the photograph. Most of the story takes place here on Earth, a simple tale of Takeru and Bismark adjusting to their new less technologically advanced surroundings. In a double-length final episode, Takeru travels back to Eden to tie up the loose ends, reminding us that this was supposed to be a dystopian tale, but for all the fanfare, plot reveals, and reconciliation, we probably could have done just as well with him staying in Florida through the ending credits. Thankfully the ending works fine as is, and we even get a adorably clumsy fistfight between Takeru and Kazuma for our troubles.

Besides Otomo’s character designs, I have to credit director Morita Shuuhei for building an America that even an American would feel nostalgic towards, with red rock country being split by highway Route 66, a group of hippies camping in the desert in a trailer while passing the nights by the bonfire, and a real post-apocalyptic Cape Canaveral as the colony that Takeru and Bismark finally reach. The majority of the cast is African-American, but we know that only by the color of their skin and fashion, not by an offensive or ridiculous characterization of them. The language barrier is dismissed without comment, but hey, with only seven episodes in total and only four on Earth there’s little time to go through Gargantia on the Verdurous Planet ’s meticulous adjustment process.

The other standout bit of animation is the opening, produced in large part by Minazaki Junpei, who seems to have no other forays into anime. I hope he does more work, because the opening fits the tone of the show perfectly, a series of fast-paced comic book style still frames interwoven with revolving shots that create a technical layout of various pieces of technology seen in the show, all set to Utada Hikaru’s strong tempo. To fit with the America theme, the comic book style is distinctly Western and there is a constant overlay of heavy dots over all the animation, making the whole opening feel like it came straight from a Roy Lichtenstein painting. In fact, the similarity is too uncanny for coincidence; his pop art was a defining style in the wave of new art movements in the 1960’s, the time that Freedom feels distinctly nostalgic for. We see a slightly different and yet equally distinctive artistic direction in the ending, featuring an endlessly branching set of pipes that would be reminiscent of a Windows screensaver were it not for the detail, sense of directed purpose in its branching, and overlay on top of the vast image of space.

Freedom is certainly a work that thrives on its atmosphere rather than its plot, but even the more ordinary story of conspiracy and a world long lost works because of how tight the pacing is while still retaining moments of space, moments that allow us to take in the rapidly shifting scenery of this post-apocalyptic world. The three stages—moon, Earth, and then back again—all take a few episodes apiece, just enough time to establish the setting and the motivation for moving to the next. Yet there’s no sense of rush, and we even get a whole episode on the road, with Takeru and Bismark experiencing the quintessential hitchhiking life without a hint of plot development. It never even needed to be in the show; their shuttle could have landed on target and that would be that. But for what? Everything that needs to happen at their destination in Florida happens with time to spare, and there’s no time for dramatic speeches or for Takeru’s crush on this unknown girl from another world to go beyond just that: a stray crush. While the 3D art style may be enough to put some people off this title, I would consider this one of Sunrise’s tightest short series’, right alongside Mobile Suit Gundam 0080: War in the Pocket , and for as offputting as 3D might seem in principle, in practice the combination of Otomo’s designs and influence, Morita’s directing, and that stray work of Minazaki to bookend it all off, it’s a joy to behold.