Almost seventy years after It’s a Wonderful Life made it into the canon of classic cinema pieces, Colorful comes to remind us that suicide is and always will be a very real problem in our society. The Japanese have a particularly strong connection to issues of depression and death when it comes to youth, who are continually pressured by their home life, their academic life, and their peers with a never-ending stream of stress and harassment that can border on torture. They attend Draconian cram schools. They face bullying and isolation. They are continually unable to fulfill their family’s unreasonable expectations. Unable to even cope with day-to-day life, children are led to seclusion, self-harm, and even taking their own lives, sometimes as early as middle school. A typical statement against suicide, particularly for youth, is that there is so much more to look forward to in life, but none of these kids have tasted such a life, and with the expectation of over a decade of schooling, there seems to be no escape.

But the most striking thing about the life of a suicide victim is how cheerful and mundane their lives may appear to outsiders, ones who do not experience their lives day after day after day, and Colorful starts by complicating this. A dead man is brought out of the cycle of reincarnation for unknown sins, but is given another chance at redemption. He inhabits the body of Kobayashi Makoto, a middle schooler who swallowed a bag of his mother’s sleeping pills to escape from his terrible life. As he dies, the unknown man enters his body and becomes Makoto, with half a year to discover his sins and repent. On first glance, Makoto has a caring mother and father, a somewhat distant older brother studying for university exams, an outgoing friendly girl whom he likes, and an incredible talent for art to supplement his general lack of academic prowess. We soon learn that his father is always at work, his mother is having an affair, his brother looks down on him, and his crush—his one and only friend in the entire school—is prostituting herself to an older man. Within a week, this unknown entity who inhabits Makoto cannot stand being at home, or eating his mother’s dishes, and while he tries to act in ways that the real Makoto never could, he starts to slide into apathy and seclusion.

By his side is PuraPura, an “angel” who guides him through the basic elements of his life until the new Makoto can fully operate on his own, as well as giving him information relevant to Makoto’s suicide. He is rarely seen in the film, just as he is rarely seen by Makoto, and this is needed for Makoto to go through his life and figure out how to live once again, trapped in an unknown body, struggling to find his original memories. They mostly insult one another in childish ways, which does help to sell their dialogue as an escape for Makoto. PuraPura is not part of the abysmal world Makoto lives in, and treats him as somewhat of a friend, something Makoto cannot truly find.

His crush Hiroka is friendly and talkative to the point of seeming completely vapid as a person. From the third person way of speaking to the desire for money to be as fashionable as adults, we are given no redeeming qualities for her as a human being. And yet the new Makoto gets a crush on her just as the old Makoto did, and he starts leading an equally vapid life to impress her. But while not saying too much, I can say that the resolution to her story vindicates both her and Makoto, and indeed the story’s view of suicide and the pressures of daily life. She also rarely appears in Makoto’s life, but serves a very specific function of leading him to realize how the original Makoto viewed the world, and why his suicide was in part due to not understanding the world outside himself.

There are a few reveals and twists, although none of them are unexpected in any way. While this seems like a criticism, it actually helps the movie a great deal. Forcing unexpected resolutions would undermine the story about the new Makoto leading a normal life, one that has happened many times before and will happen many times again. He originally sees the life of Makoto as mundane, but in short order grows to think of his trials as unique and exceptional. We, as observers, know better, and can watch as his attempts to express his abnormality ultimately lead him to find happiness in normality. This is a strong case against suicide, much more than simply saying “it gets better”. Suicide is an ultimate act of abnormality, one that rejects the world and its hypocrisy that only the victim is privy to. In reality everyone has to deal with their own issues, and sees what is wrong in the world; even so we all have a place to enjoy life and contribute something to improve the lives of others, all while relying on others to improve our lives as well.

But in addition to having few twists, the characters themselves don't seem to grow outside their paradigms. Every character aside from Makoto exists in the story only to serve as a way of exposing more and more truths about his life and the futility of suicide, and so none of them receives any true resolution in terms of their own lives. It is unfortunate that Colorful does not have a stronger cast of characters, given that the point of the film is to draw us into Makoto’s human experience. While the setting feels fresh and plausible, most of the dialogue and developments are somewhat canned, and the drama sometimes skates the line of being contrived. The primary suspect for this is actually not the dialogue itself, but the background music, which is about as heavy-handed as possible. Every time the music enters, the film is forced to step away from its characters, instead blatantly telling us to feel something irrespective of the actual weight of the events on screen. As a result I felt very little where I may have otherwise felt a genuine reaction of sympathy and understanding.

The theme of art is only tangentially related to the events that transpire, and thus the title of Colorful feels entirely forced with regards to the idea that the lives of people are less monotonous and more vibrant than they often perceive. It makes for a good line—one beyond the wisdom of the 13 year olds saying it—but very little actually suggests it. Excepting Makoto, Hiroka, and at times Makoto’s mother, every other character is almost completely colorless, forcing Makoto to create a spectrum of colors that define his life out of a few empty tubes of paint. The use of metaphors like art falls somewhere between abstract parable and concrete worldbuilding, ultimately falling short of both. Overall Colorful lives and dies by mundanity and symbolism, and while this proves its points about suicide well, it detaches us from the experience of the story itself.

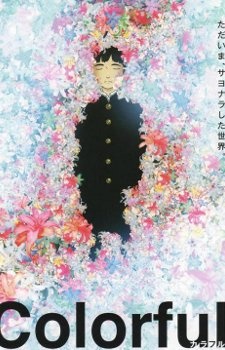

I certainly think that animation was the correct choice for Colorful, as it gives the experience of coping with the world a dreamlike quality, and puts bleak developments and personalities at right angles with a vibrant palate. Added to this is a slightly abnormal (but not at all unappealing) design, and a few scenes are rendered with simple 3D modeling that absolutely works at conveying a sense of surrealism appropriate for scenes involving the essence of death and life. In many ways, Colorful succeeds in telling its parable in a meaningful and enjoyable way despite not quite succeeding at convincing us of the actual experience of learning it.