It's an in-joke among longtime anime fans—or perhaps a shared wisdom that comes with experience—that the old kids shows have all the best animation and even most of the best emotional scenes. For as much as it's easy to write off the Cardcaptor Sakura fans as nostalgia-fueled and lacking in critical taste, anyone going back to the show nowadays would be struck by not only the comedy and great characters but also the beautiful late 90's cell art, the framing, and the playful animation all around. And the 90's weren't a blip; a decade earlier My Neighbor Totoro brought the name Miyazaki Hayao into more households than ever with the image of family and the heartland, and a decade before that we saw Anne of Green Gables, Manga Nippon Mukashibanashi, and Little Jumbo. In terms of what distinguished these, Anne brought stunning landscapes and the subtlety of everyday life, Manga Nippon Mukashibanashi delivered an array of different traditional tales with quirky styles, and Little Jumbo took musicals to the anime screen, with a cheerful array of faces and character animation complete with the stark lighting and pastel colors of Tales from a Street Corner. In fact Tezuka's early animation is more and more apt a comparison whenever I look back; it's a story of war and peace, despair and hope, and in thirty minutes it delivered the fullest range of emotions a children's work could contain and possibly more.

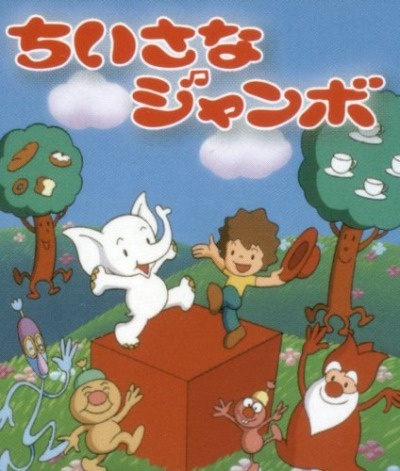

The first image that came to mind when I heard the title was Dumbo, albeit for the stupid reason that “umbo” isn't the most common suffix out there, particularly not for kids stories. The second thought was Little Nemo for another obvious and dumb reason, which turned out to be fair since they both shared director Hata Masami, but Dumbo was the more fair comparison simply by virtue of the main character being a tiny circus elephant. Jumbo and his trainer Baloo arrive on a peaceful and lush island in a little red box, entertaining the king and handful of other inhabitants with their performances. The whip Baloo uses, he explains, isn't for hurting Jumbo, but rather just gets him excited with the cracking sound. He cracks the whip in the air and an excited Jumbo stands on his front legs and walks about. While the first song before they came to the island featured the king poking and prodding his subjects to get them to be less lazy, even his chastising comes across similarly benign, not meant to harm but to encourage. This is a kingdom of happiness, made even more exciting by this performing troupe of Jumbo and Baloo. With their squat figures that accentuate their big smiles, it's plenty clear.

And like Tezuka's harmonious street corner, it's this cheerfulness that makes the sudden appearance of war and famine so much more potent. Both works understand that the potency of the war comes from our small world being the unlucky bystander rather than the target. Two islands hurl blue and pink cannonballs at each other with the island right in between, and suddenly the shading that came with warm sunsets a few minutes earlier take up half the screen, the other half being the pale flashes of the destruction around. The art of Little Jumbo being as simple as it is, it's these stark monochromatic shots that make the world feel hostile, and it brings attention to the fact that the earlier scenes had simple but vibrant colors. A red apple or yellow banana can feel inviting even if the rest of the shot is just one or two other colors, maybe a green or blue, but suddenly the screen is nothing but red and black, and nothing seems inviting anymore. The pace of the opening numbers seems slow as if to appeal to kids, but it soon becomes the one happy intermediate between frenetic cuts and dead silence.

Another note about the shadows: in the early moments they would always face towards us with a light source behind the cast, or at least be on the ground where they feel harmless. The chilling second act of the story uses classic horror shadows, towering above the characters on the rock faces behind them. The fog obscuring the distant mountains, the dimly lit jagged mountain paths with pitch-dark drop-offs on either side, and the sudden prominence of shade on the characters' faces are enough to create darkness all around, even as the characters keep their bright palates against this backdrop. And the shadows mirror a loss of hope; without spoiling the songs in this section I can say that it felt heartbreakingly tragic, because despite being a kid's story the despair and desperation of a broken world overwhelms the cast immediately, and the early happy numbers echo back with sinister irony.

Of course everything finds its way back to happiness and joy—even Tales of a Street Corner had a lingering final shot of flowers breaking through the ruins—but I'm amazed at the depths the story's tone went to. Creator and director Yanase Takashi is instantly recognizable by his button-nosed characters as the creator of the joyful Anpanman, but the themes at play in the second act are unrecognizable. Going through his work at Sanrio we actually find a number of stories with a similar darkness, from Ringing Bell to Rose Flower and Joe, and unfortunately for us it always seems to have to do with cute animals. Though none of the work's three directors, Yanase, Hata, and Hirata Toshio, directly worked on Tales of a Street Corner, they all worked at Tezuka's Mushi Pro until it folded and so it's not crazy to think they picked up the overarching story and themes from his early masterpiece. Another potent similarity between them is the musical format. Tales had no words so it was solely in the tone of the tunes, but Izumi Taku's songs for Little Jumbo carry all the emotions, both high and low, to a terrifying degree. I thought back on a similar experience with Broadway's Next to Normal, particularly when the early songs come back to haunt us in this middle section. It was a brilliant structure and it even helped to raise my spirits when the upbeat closing came to bring us back into the light.

There's something very satisfying about the whole experience of Little Jumbo, short as it is. There are moments where it's clear how simple the images are, like a sunset being conveyed through a rainbow banding of various reds and purples or the group of Jumbo and Baloo's fans bobbing up and down to their performance. The story is equally simple, ending with an inevitable deus ex machina. But it's these simplicities that convey something profound, whether it's on the damage of war or just the way that color, framing, and music can build a whole emotion even before filling in the plot and visual details. It built the character of the king with just two or three numbers, from his strictness to his love of his subjects to his misguided but pure sense of wanting to protect them. It builds the bond between Baloo and Jumbo even in their darkest moments, and uses Baloo as a complex and conflicted human set against the pure joy and mischievous curiosity that never leave his partner. It gives a new meaning to the fact that, as a story of holding onto humanity in the face of tragedy, Little Jumbo is named after him.