Maybe I treat The Boy and the Beast too harshly. Maybe if it had come from the director of lesser works than Hosoda Mamoru, one of the most talented anime movie directors poised to fill the international void Hayao Miyazaki is leaving in the wake of his retirement, I could even recommend the movie as an above average rendition of many tired old trends keeping both anime and film running in perpetual circles. But the director of Summer Wars knows how to make a well-paced action film, and the director of The Wolf Children Ame and Yuki certainly knows how to form a strong emotional web of human maturation. Mamoru happens to be both of those people, and so it is absolutely the case that he should know better than to leave both key storytelling aspects to the dogs and expect them to hold up a movie with little else.

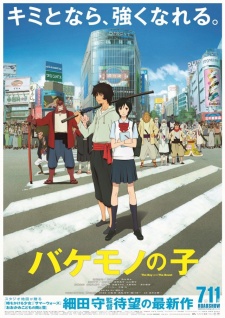

Many shots from the opening sequences are reminiscent of his other works, from the duller-colored flashbacks of a young boy left orphaned and unwanted by his family to the dirty but flashy streets of Shibuya where he lives on the streets in solitude, to his accidental wandering into an alleyway that eventually leads to the feudal wonderland of the spirit world, filled with lanterns and figures of all shapes and sizes bustling about. It is a crowded and yet sterile Miyazaki-esque fantasy world, an odd contrast to the homogeneous concrete jungle we first see. The boy is quickly picked up by a large red bear named Kumatetsu, who makes the boy his apprentice on a passing drunken whim and names him Kyuuta. The aged leader of the spirit world has announced a tournament to determine his successor, and the two warriors most poised to take the throne are Kumatetsu and the widely respected and orderly Iouzan. Kumatetsu is strong, certainly strong enough to teach an apprentice the ways of the warrior, but he is lazy, always drunk, and not nearly disciplined enough to challenge Iouzan, who devotes every moment to training and working for the public benefit.

But why should Kumatetsu win, when all he does is drink and slack off on his training? No matter how much the presence of the feral boy Kyuuta in his life eventually leads both of them to become stronger beings worthy of respect, it is clear that Iouzan has the discipline, focus, and benevolence to lead the spirit world in the right direction. And yet the plot demands that Kumatetsu the underdog be the unlikely hero that rises from the ashes of his former self, despite us being given absolutely no reason to spurn Iouzan or his convictions. It simply gives a goal for Kumatetsu and Kyuuta to move towards, to nucleate around in order for their characters to improve. What is left in the wake of their challenge to power is an unexpected force that moves against them out of anger, which escapes into the human world and wreaks supernatural havoc around Shibuya. Even when we trust the two to come together and stop the destruction and save the day, the fact is that had those two not escaped their unfortunate circumstances, there would be no ruined streets and traumatized people running about in panic. Are they at fault? Not particularly. And yet it makes it hard to treat them as heroes when they brought this force into the world, however inadvertently.

Unfortunately there are few other characters to sympathize with. They fall neatly into side characters that serve to heighten the day-to-day comedy and the characters that push the plot along, with absolutely no overlap or depth of character. There are some glimpses of dimensionality provided by Iouzan’s first son, Ichirouhiko, who struggles between his unyielding respect for the good his father does in the world and the sense of loneliness from his father committing to that good over his parental responsibility. However, his scenes quickly progress from frustration and misguided confused anger to plot-driven supernatural powers that pigeonhole him into being a generic angry “antagonist”, and whatever sympathy we have for his character disappears with…well, his character.

I suppose the human girl Kaede who approaches Kyuuta and begins to direct his sense of purpose and meaning deserves brief mention, only in that for however much of a backseat she plays in order for Kyuuta to save the day, they at least don’t explicitly end up together in some contrived love story cooked up in the latter half of the movie for more artificial layers of motivating the events on screen. She grounds him and gives him an outlet for his humanity, motivating him to study and find balance in his parallel lives between worlds. Thankfully this ends up being relevant to the final outcome of Kyuuta’s life, as well as his ability to save the day in the end. With that said, it was clearly too much to ask for her to have any physical strength, putting her at the mercy of both generic thugs and Kyuuta the martial artist. Men are the brawn, and the single woman is the brains and the heart put together, until another man comes and takes that role from her as well. The Boy and the Beast is a movie steeped in ridiculous masculine posturing, from the treatment of its characters to the laughable fact that it expects us to care that the stronger fighters win and take on roles unsuited for them as soon as they clean up their bestial personalities.