Dec 5, 2025

Beyond the Fork: Is High Entropy Enough?

Investigating 'Silent Errors' in LLM Reasoning—where models are confident but wrong.

Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Reward (RLVR), popularized by methods like DeepSeek’s GRPO, has changed how we optimize reasoning models. Instead of a complex critic, we simply verify the final answer and let the model figure out the rest.

Recent research (Wang et al., 2025) suggests a “80/20 rule”: that reasoning is driven almost entirely by a minority of “Forking Tokens”—moments of high entropy (uncertainty) where the model chooses a path. The implication? Low-entropy tokens are just structural fluff.

We challenge this assumption.

We investigated whether low-entropy (confident) tokens are actually “safe,” or if they harbor hidden failures.

The “Silent Error” Conjecture

If a model is uncertain (High Entropy), it’s exploring. But what happens when the model is highly confident (Low Entropy) but completely wrong?

We hypothesize the existence of Silent Errors: tokens where the student model is sure of itself, but a stronger “teacher” model strongly disagrees.

These represent “confident hallucinations” or rigid bad habits that standard RLVR might miss because the gradient signal at low entropy is often weak.

Experimental Setup

We set up a distillation environment to test this:

- Student: Qwen2.5-3B-Instruct

- Teacher: Qwen3-8B (Reasoning Enabled)

- Task: MATH500 (Level 5 problems)

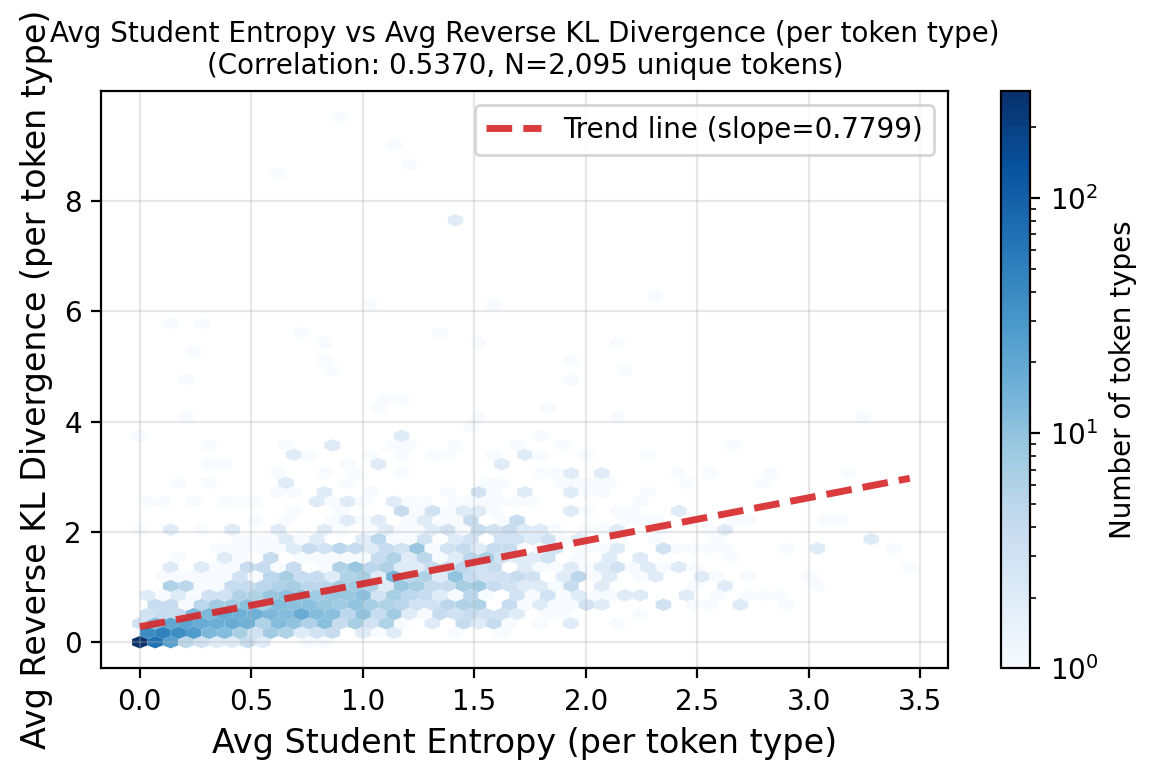

We compared the Entropy of the student against the Reverse KL Divergence (disagreement) with the teacher for over 300k tokens.

Finding 1: The Blind Spot

Standard theory suggests a linear relationship: if the model is confident (low entropy), it should be aligned with the teacher (low KL).

However, our data reveals a Correlation Anomaly.

Figure 1: The “Blind Spot.” The top-left region highlights tokens where the student is confident (Low Entropy) but the teacher strongly disagrees (High KL).

Figure 1: The “Blind Spot.” The top-left region highlights tokens where the student is confident (Low Entropy) but the teacher strongly disagrees (High KL).

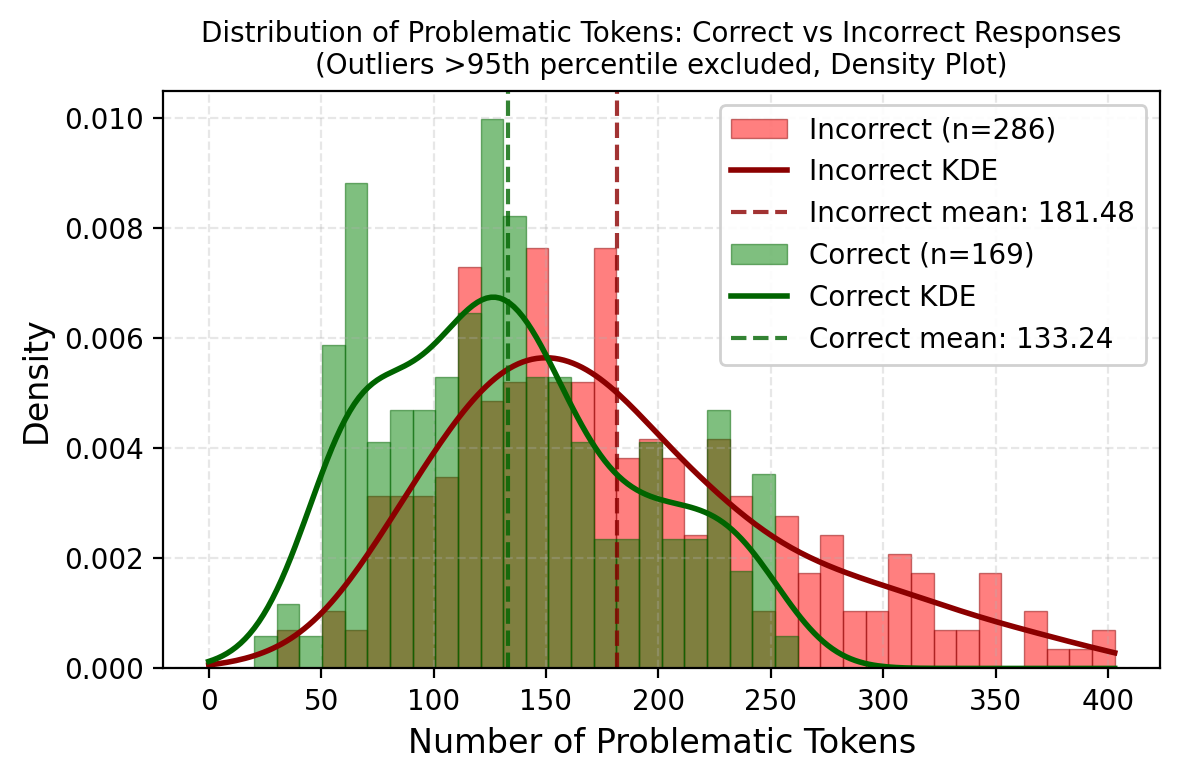

Finding 2: Confidence Correctness

Do these “Silent Errors” actually hurt performance? Yes.

When we separated the reasoning traces into Correct and Incorrect final answers, we found that incorrect paths were plagued by these problematic tokens.

Figure 2: Incorrect responses (Red) have a significantly higher density of silent errors compared to correct responses (Green).

Figure 2: Incorrect responses (Red) have a significantly higher density of silent errors compared to correct responses (Green).

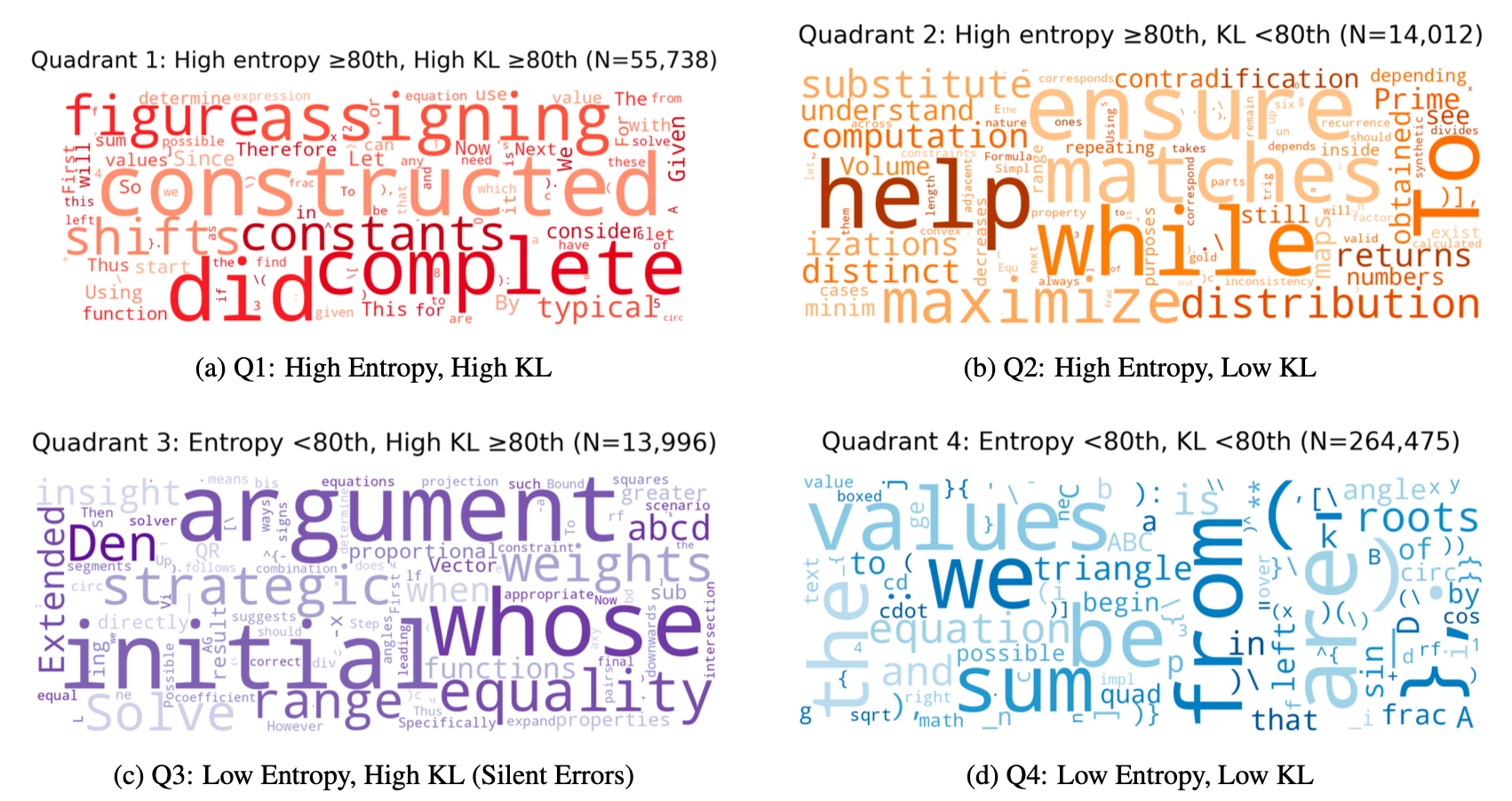

What are these tokens?

We calculated a “Problematic Score” () to find the worst offenders—tokens where the model is most confidently wrong. We identified two distinct failure modes:

1. Syntactic Rigidity

The model obsessively sticks to specific formatting (like LaTeX brackets) even when inappropriate.

2. Premature Logical Commitment

Tokens like To, First, or implies act as logical pivots. The model confidently dives into a reasoning path that the teacher knows is a dead end.

| Rank | Token | Count | Problematic Score | Pathology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | lf | 107 | 114.84 | Formatting Artifact |

| 2 | \[ | 1771 | 55.21 | Syntactic Rigidity |

| 4 | To | 407 | 13.30 | Logical Pivot |

| 6 | First | 209 | 10.64 | Premature Commitment |

Figure 3: While high-entropy tokens (Forking tokens) look like reasoning choices, silent errors look like rigid structural commitments.

Figure 3: While high-entropy tokens (Forking tokens) look like reasoning choices, silent errors look like rigid structural commitments.

Conclusion

The prevailing view that we only need to optimize “Forking Tokens” (High Entropy) is incomplete.

While high-entropy tokens may control the direction of reasoning, low-entropy silent errors often control the quality of execution. If we ignore these “confident hallucinations,” we leave a significant portion of reasoning failures unaddressed.