Dec 1, 2025

CausalPool: Do VLMs Learn Physics or Just Match Patterns?

Investigating the 'Causal Disconnect' in Vision-Language Models through counterfactual supervision.

CausalPool: Eliciting Causal Behaviour through Counterfactual Supervision

Paper & Resources:

- 💻 Training Code: ScottCTD/causal_pool_training

- 🎱 Data Generation: ScottCTD/causality_data_generation

- 💾 Test Set: Download Data

Do Vision-Language Models (VLMs) actually construct internal world models of physical dynamics? Or are they merely sophisticated “causal parrots”?

While a model might correctly predict that a glass will shatter if dropped, does it understand the why and how, or is it just correlating images of falling objects with broken shards?

In our paper CausalPool, we investigate this by testing a fundamental hypothesis: If a model can reason counterfactually (simulating “what if”), does it necessarily understand the physical reality (“what is”)?

Our results uncover a surprising Causal Disconnect.

🪜 The Ladder of Causation

To distinguish between correlation and true understanding, we use Judea Pearl’s Ladder of Causation.

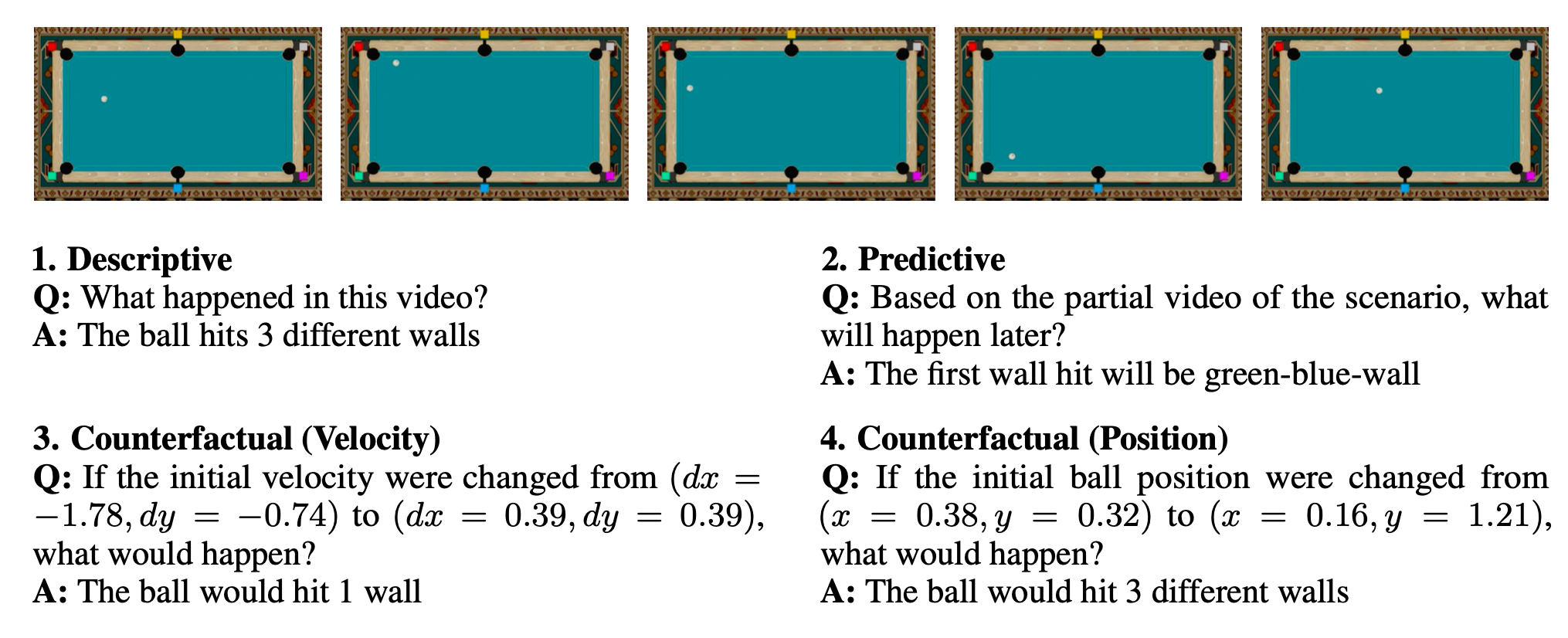

Figure 1: Overview of the CausalPool Dataset. We test models on Descriptive queries (Rung 1) and Counterfactual queries (Rung 3) involving continuous physics variables.

Figure 1: Overview of the CausalPool Dataset. We test models on Descriptive queries (Rung 1) and Counterfactual queries (Rung 3) involving continuous physics variables.

- Rung 1: Association (Observation)

- “What happened in this video?”

- Requires robust perception.

- Rung 2: Intervention (Action)

- “What if I do X?”

- Rung 3: Counterfactuals (Imagination)

- “What would have happened if the ball started faster?”

- This is the highest form of reasoning. It requires abduction: inferring the hidden state of the world from observation, then modifying it.

The Top-Down Hypothesis

Intuitively, Counterfactual reasoning should be the hardest task. To simulate a deviation from reality, you must first correctly perceive reality. Therefore, training a model to master Rung 3 should force it to master Rung 1.

We set out to test this top-down learning curriculum.

🎱 Introducing CausalPool

We introduce CausalPool, a synthetic video benchmark generated via the Pooltool physics engine. Unlike previous benchmarks that rely on discrete collisions, CausalPool focuses on continuous variable interactions (velocity vectors, friction, angular momentum).

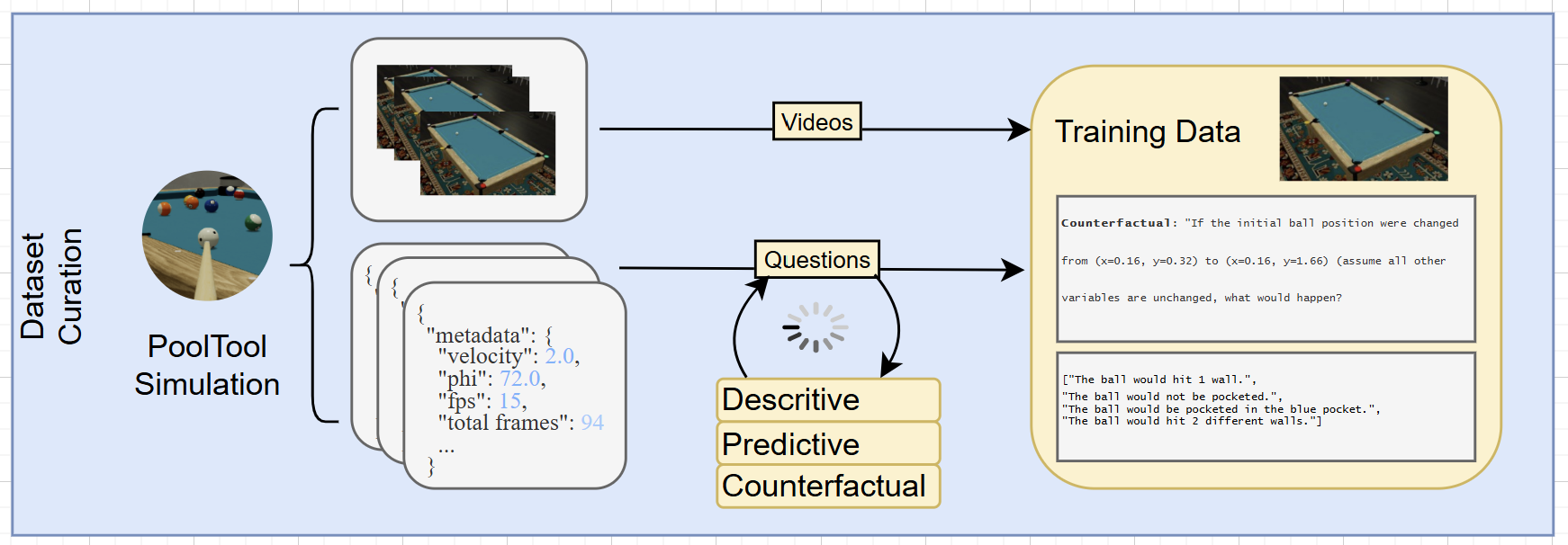

Figure 2: Data Generation Pipeline. We generate 16,384 video clips with precise metadata. We then synthesize questions that blind the model to “what is” while quizzing it on “what if.”

Figure 2: Data Generation Pipeline. We generate 16,384 video clips with precise metadata. We then synthesize questions that blind the model to “what is” while quizzing it on “what if.”

- Total Clips: 16,384 (single-ball scenarios)

- Interventions: Precise changes to Position () and Velocity ().

- The Experiment: We trained specialized models (Qwen3-VL-4B) exclusively on specific rungs of the ladder to see if capabilities transfer.

📉 The Causal Disconnect

Our experiments revealed a counter-intuitive result that challenges the “Top-Down” hypothesis.

We trained a model exclusively on Counterfactual queries (“If speed doubled, what happens?”). We expected this model to learn the underlying physics and thus be able to describe the original video.

It failed.

| Model | Training Data | Rung 3 Accuracy (Counterfactual) | Rung 1 Accuracy (Descriptive) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Chance | - | 25% | 25% |

| Zero-Shot Baseline | None | ~27% | ~38% |

| CausalPool-Desc | Descriptive Only | 38% | 84% |

| CausalPool-CF | Counterfactual Only | 70% | 45% |

Key Findings:

- The Specialist: The model trained on counterfactuals (

CausalPool-CF) became excellent at counterfactuals (70% accuracy). - The Failure: That same model showed negligible improvement on describing the video (45%) compared to the baseline.

- The Conclusion: The model learned to be a “Blind Simulator.”

It learned a function to map linguistic interventions to outcomes via shortcut mechanisms, without grounding these predictions in the visual reality of the video.

👁️ The “Blind Simulator” Phenomenon

The failure is best illustrated qualitatively. In the example below, the model correctly answers a complex math-heavy counterfactual question but hallucinates events in the actual video.

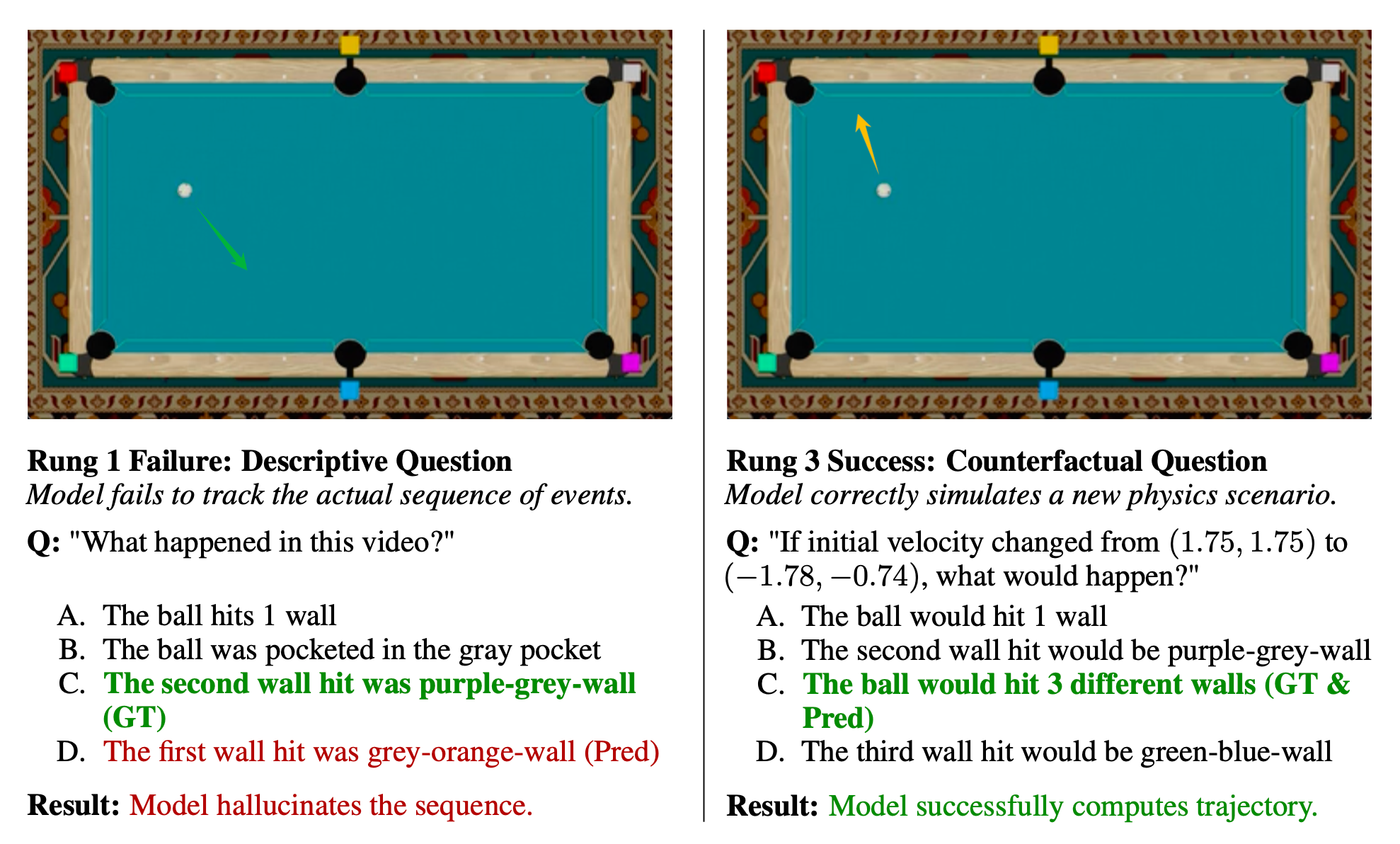

Figure 3: The Causal Disconnect. (Left) When asked “What happened?”, the model hallucinates a wall collision (Option D). (Right) Yet, when asked to simulate a hypothetical trajectory where the velocity is inverted, the model correctly identifies the outcome (Option C).

Figure 3: The Causal Disconnect. (Left) When asked “What happened?”, the model hallucinates a wall collision (Option D). (Right) Yet, when asked to simulate a hypothetical trajectory where the velocity is inverted, the model correctly identifies the outcome (Option C).

- Rung 1 (Reality): The model hallucinates a wall collision that never happened.

- Rung 3 (Imagination): The model correctly simulates a complex trajectory change.

This suggests the model solves the reasoning task by bypassing the visual encoder in favor of learning language-based transition dynamics. It solves the math, but it ignores the pixels.

Future Directions

Our work demonstrates that Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) is insufficient to induce robust physical world models. Current architectures can decouple logical reasoning from visual perception. To bridge this gap, future work must move beyond next-token prediction toward Causal Reinforcement Learning or neuro-symbolic grounding.