In Fall 2024, the New York Police Department was the subject of international media attention, after two officers chased and confronted someone who didn't pay their public transit fare. The officers fired their weapons several times, shooting the suspect, a hospital worker on the way to their job, another bystander, and one of the officers themselves. I learned about the incident by way of reporting by the BBC. By my count the article contains about 13 paragraphs worth of quotes, direct and indirect, from state bureaucrats (the police commisioner, Mayor Eric Adams, NYPD Chief of Department, the chief executive of the MTA, an NYPD spokesperson) and only 3 paragraphs representing civilian perspectives (a public defender, relatives of the hospital worker, and a protestor).

The civilian's perspectives were rather critical of NYPD conduct:

The state bureaucrats tended to be uniformly more defensive:

So, this article gave more air time to accounts that were favorable to the NYPD than critical of it. I was curious whether coverage of Canadian deadly force events was similarly imbalanced. I couldn't find much in the way of scholarly work on this topic so I decided to take it on myself, along with some colleagues from the University of Toronto and University of British Columbia.

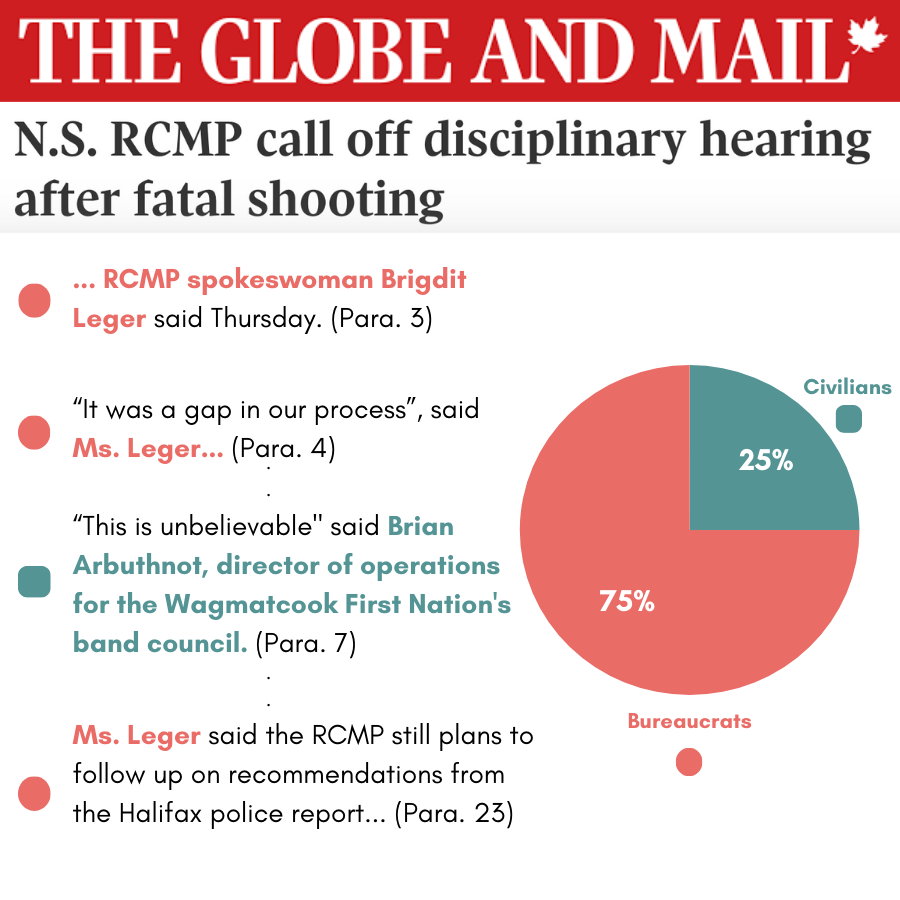

We analyzed 4,000 news articles pertaining to deadly force incidents, where civilians are killed in an interaction with the police, to look at whose points of views are recorded in them. We categorize people, or groups of people, into state(-aligned) actors (police officers, police union representatives, crown attorneys, coroners, police oversight bodies, etc), and civillian actors (friends, family members, family attorneys, witnesses, etc). We then developed a model that can take a paragraph and classify it as representing the Point of View (POV) of a state actor or a civillian (or neither). Here's an example from an actual Globe and Mail article:

If this were the whole article, then state representation would be 75%; civillian representation would be 25%.

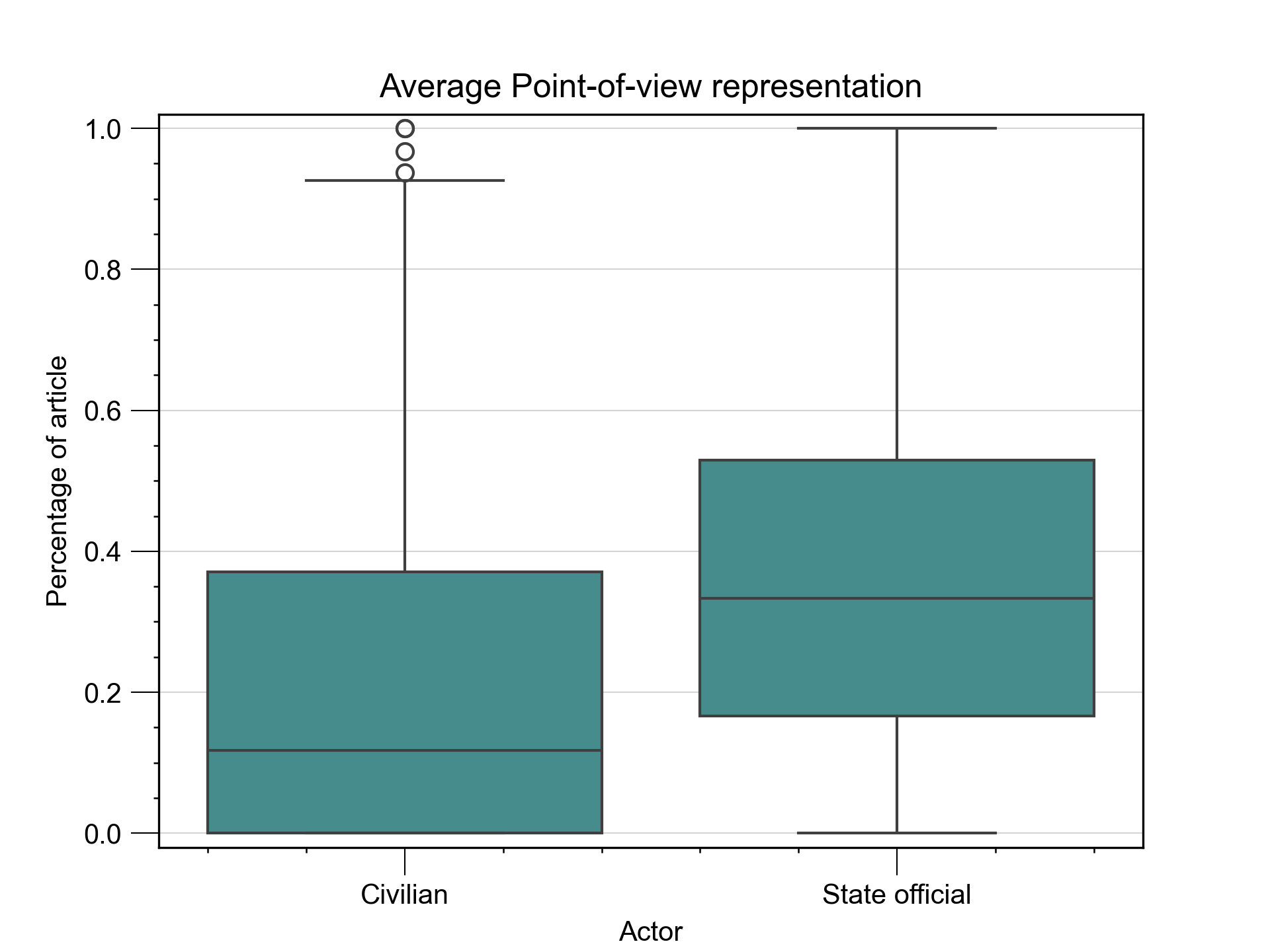

We computed the same statistic on each of the 4,000 articles in our corpus, from a wide array of news outlets, from local ones like The Toronto Star to national ones like The Globe and Mail. We found that the average article contains three times as many passages explicating on the POV of state actors than those of civilians:

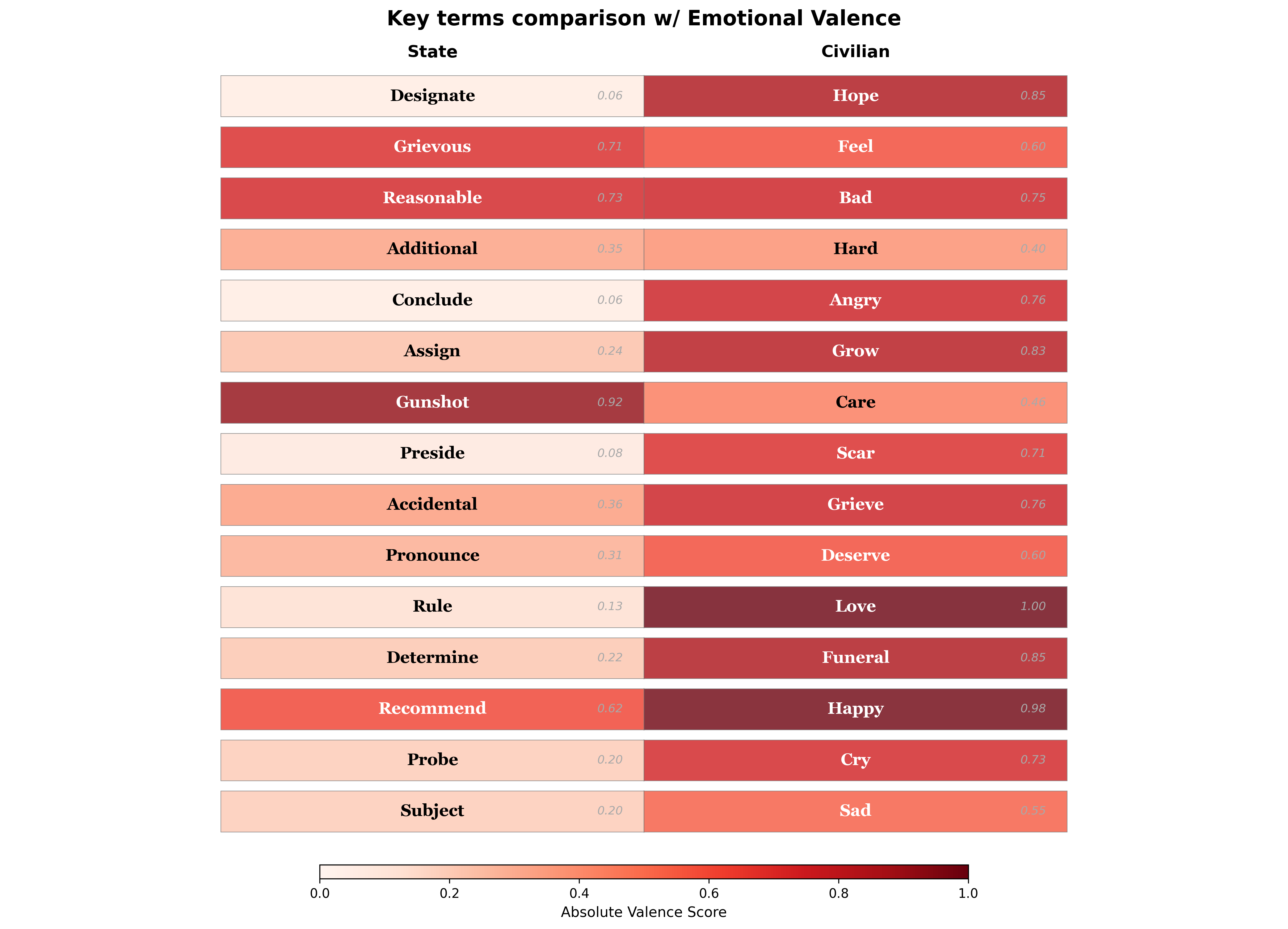

So, state bureaucrats tend to get a lot more airtime in presenting their perspectives. Let's look at how their POVs on these incidents differ. There are tens of thousands of passages for both groups across these articles, so instead we'll work with a summary of sorts: the most frequent discourse terms in state POVs vs. civilian POVs. Here are the top-15 terms for both groups.

They're clearly rather different. State bureaucrats POVs, perhaps unsurprisingly, have alot to do with bureaucracy: designating, assigning, pronouncing, ruling, etc. This is not exactly happenstance; there is a known effort by Police Media Units (PMUs) to make statements around deadly force incidents as minimal and impersonal as possible, tending to use euphemisms to minimize the potential for evoking public outrage, as documented by Walby and Alavi in their 2022 publication Examining Press Conference and Press Release Accounts of Canadian Police Shootings. For example, in our corpus victims are described as dying from 'sustaining gunshots', rather than the more natural linguistic construction "shot by the police." Consider (randomly selected) examples below:

To the extent that an emotionally-provocative term like grievous is used, it is not actually about the nature of the grievous injury incurred by the victim, but rather that the officer in question felt that they were at risk of being grievously injured by the victim:

By comparison, the discourse patterns from civilians are highly emotive. Consider the distribution of emotional valence scores:

Looking at the terms for civilian discourse, we can see first and foremost that there is a strong desire for change; Consider the fact that the most distinctive discourse term for civilian POVs is hope:

While the discourse patterns evoked by state bureaucrats is that the bureaucracy is churning along as it was designed in handling the incident, the invocation of hope by civilians demonstrates the anxiety that it likely won't achieve the outcomes that they are looking for, a desire for reform whether implicit (first quote) or explicit (second quote).

There are also references to grief for the surviving family members and associates:

And of course, outrage (angry):

Example 1: "I wanted to be taken seriously. I didn't want to seem like a hysterical family member who's just so angry that I'm just saying things," Kylee said in the interview. "The questions that I have are meaningful and they are coming from somewhere important."

Example 2: Norm Assiff, who is representing Hanna's estate, said Hanna's sister, Susan Bandola, is "angrier and left with more questions than answers" in the wake of the ASIRT report.

Example 3: Burke's mother says the justice system failed her son and is to blame for his death. Her anger is stronger than her grief. Llama says, "I am very sad. Not only for myself. But I'm very angry at the system. What the judge did. Or what he failed to do."

Example 4: In a statement Friday night from leadership on the Montreal Lake Cree Nation Inter-agency Facebook group, they extend condolences to the McDonald/ Charles families, while also acknowledging the impact the incident on Dec. 14 has had on the entire community, encouraging those feeling angry, sad or with questions, to reach out to local grief counsellors.

These are two wildly divergent bodies of discourse. And a considerable representational gap between the two, that is fairly robust across across jurisdictions and reporting outlets.

If you agree that the press should serve as the Fourth Estate in holding institutions to account, then I think these results are concerning. We should have a higher bar for news organizations is to disseminate more than just opinions from state bureaucrats, especially when it is the efficacy of the said bureaucracy that is under scrutiny.

If we simply wanted to know the opinions of punishment bureaucrats, then why not just verbatim publish the press releases put out by Police Media Units? I ask this rhetorically. But this model of journalism is not unpopular among media scholars and practitioners. Most famously, Walter Lippmann a prominent journalist and media theorist put forth this model in his monograph Public Opinion believed civilian opinion to be too malformed to merit coverage, and believed that journalists role should be akin to disseminators of expert opinion.

This is far from consensus though. John Dewey most famously argued against this in his monograph The Public and it's Problems, basically arguing that in order for the public to govern itself in a democratic republic, it needs to continuously discover and understand itself. And there is no way to do this without interaction and input from the broader citizenry:

"The man who wears the shoe knows best that it pinches and where it pinches, even if the expert shoemaker is the best judge of how the trouble is to be remedied."

I think Dewey's case is well borne out by this data, the picture we get from civilians — a punishment bureaucracy that, especially in the case of deadly force incidents, often fails to deliver satisfactory outcomes — is quite distinct from the one that we get from state bureaucrats. There is no way for the republic to reform itself without understanding the conditions on the ground; elected officials and voters alike need to hear more from people who have been directly afflicted by police brutality. We already know that this can lead to meaningful reforms with bipartisan consensus: the Special Investigations Unit, the first police oversight board in the country, was only formed after eliciting opinions from racialized minorities according to Toronto Professor Akwasi Owusu-Bempah's PhD dissertation. These solicited accounts from racialized minorities revealed widespread outrage and feelings of betrayal towards the punishment bureaucracy, sentiments that can otherlead to broader loss of faith in democratically elected governments, and withdrawals from democratic processes [source]. The SIU was borne out of such conditions, and, while it has received its fair share of criticism, it has on occasion delivered prosecutions for unwarranted uses of force that may not otherwise have been achievable.

There is space for journalists who want to do more critical crime reporting work, specifically when it comes to deadly force incidents. It should be acknowledged that reducing the POV gap between civilians and state bureaucrats is a tall order. There is infrastructure in place to ensure that state bureaucrats can get their voices perspectives printed in the news: They have public relations offices for this express purpose. There is thus an inherent structural bias that prevents critical civilian voices being heard with the same expediency, it takes a high degree of journalistic labor to become acquainted with family and community members such that they are willing and able to provide their characterizations of the complex personhood of the victim, and any contests to state bureaucrat's versions of events.

But there is scope for other organizations to fill in this gap to some degree. Civil liberty organizations, the CCLA, the John Howard Society, perhaps academic groups, for example, should work together to build the same infrastructure that provides more critical context to the media. This doesn't necessarily require intimate details of developing cases. Even providing broader context makes a difference. For example, these organizations could answer the following questions for journalists: Is this incident an aberration or does it belong to a series of excessive force incidents over the years? Who staffs police oversight boards, and how often do they lay charges against police officers? If charges are laid, how often do crown prosecutors elect to drop the charges? If the crown prosecutor pursues the case, how often does the case lead to an acquittal versus a prosecution? In a word, what should the public expect of the bureaucracy as it currently stands, and how can it be reformed to better meet the public's needs?

How do I replicate the analysis?

We provide our analysis dataset here. It includes the article titles, outlets, incident dates, publication dates, and predictions for each paragraph in the article. The predictions column is an ordered list of 2-tuples, where the first element is the first word in the paragraph, and the second element is the label for the paragraph.

Can I run the model on new articles?

Yes, see here.

How robust is the deference to state bureaucrats across outlets?

It is incredibly robust, whether we're talking about the CBC, Toronto Star, Globe and Mail, National Post, CTV, Global News, and so on. The disparity is not quite as large for the Toronto Star (23% civilian passages vs. 33% bureaucrat passages) as the overall average (12% vs. 36%). It is larger for the National Post (12% vs. 40%). It is the largest for Global News and CTV, that have quite a few articles with little to no civilian representation.

What are some more examples of more balanced or critical coverage?

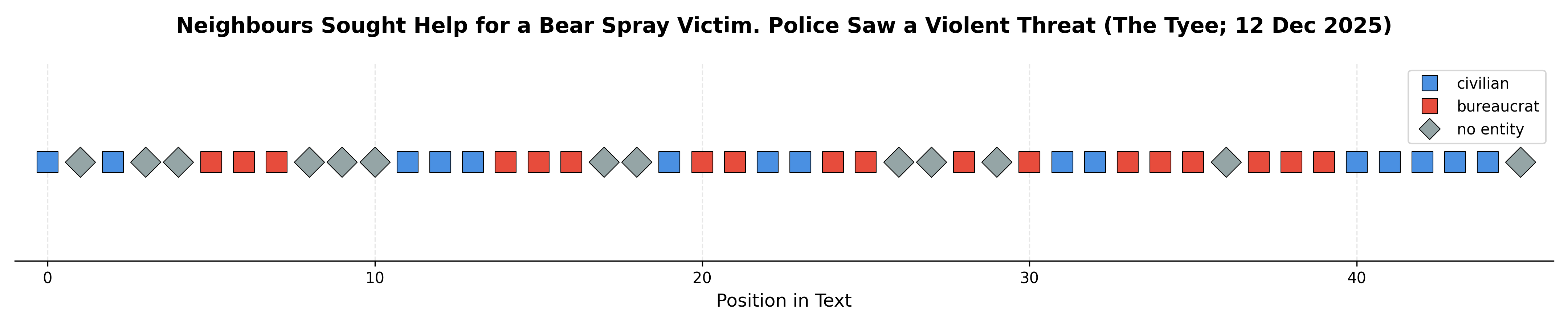

Have a look at this example from The Tyee:

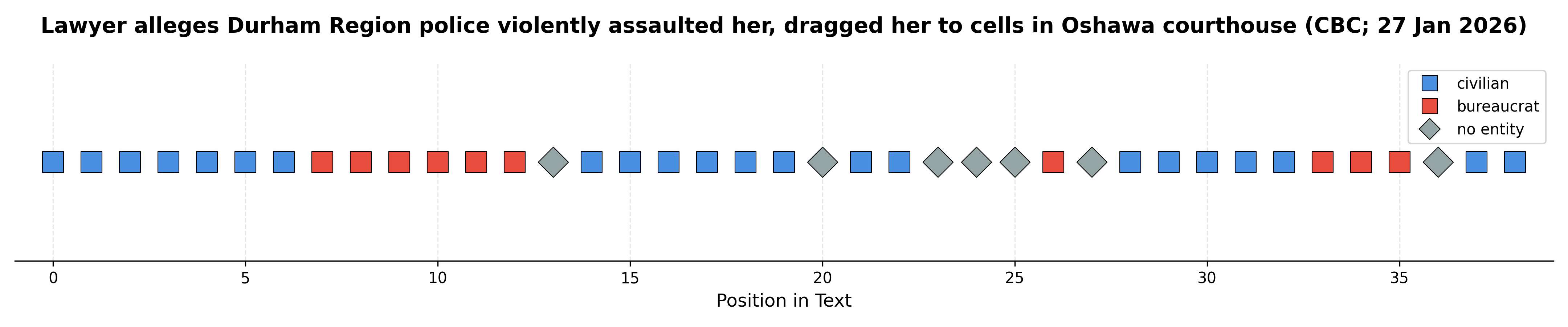

Or some highly critical coverage from the CBC just this past month, where a lawyer alleged that they were violently assaulted by Durham Region police:

Again, it should be acknowledged that these are huge outliers compared to the majority of articles on this topic, where bureaucrats are afforded 3 times as much coverage on average relative to civilians.

How do I find a record of all deadly force events in Canada?

See CBC's Deadly Force database, and the Tracking Injustice database collected by researchers at Carleton, Queen's, and University of Toronto. See also The List of Killings by Law Enforcement Officers in Canada on Wikipedia.