Session Fixation

By: James Lahey, Nadia Hassaan

Table of Contents

Introduction

Session fixation attacks attempt to exploit the vulnerability of a system which allows one person to fixate (set) another person's session ID. In other words, session fixation is an attack that allows an attacker to predetermine the session token value used by a victim.Attack Overview

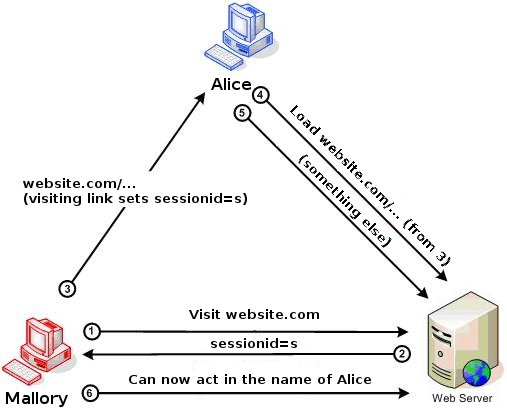

A general session fixation attack is illustrated in the following diagram.

The scenario described in the diagram can be viewed as consisting of 4 steps. We will use the usual

nomenclature to describe the various roles in the attack. The context of the attack is as follows.

Mallory wants Alice to use some session s (which Mallory knows, and can then use) on some website w.

We will refer to the web server hosting w as ``the web server''. To make the diagram clearer, we took w to be website.com; the discussion will refer to it as w. The malicious URL referred to below as u is referred to as ``website.com/...'' in the diagram.

Step 1. (Refers to (1) and (2) in the diagram)

Mallory visits w. Mallory obtains a session ID s which the web server regards as being a valid session.

A crucial assumption from this point on in the attack is that s remains a session ID which is considered to be a valid session ID (i.e., it doesn't expire).

Step 2. (Refers to (3) in the diagram)

Mallory crafts a URL (on w's domain) u such that when u is visited by some user A, A's session ID for w is set to s.

Step 3. (Refers to (4) and (5) in the diagram)

Mallory gets Alice to load u, and do something else (when loading u is all that Mallory wants, "something else" could be nothing).

Step 4. (Refers to (6) in the diagram)

Mallory can now act in the name of Alice, because Alice and Mallory are using s.

It is important to keep in mind that the basic structure of the attack only involves sessions. It has nothing to do with passwords, accounts, or logging in or authentication. Of course, often these attacks will involve some of these elements. In this case the attacker will want Alice to do more, e.g., login (this is an example of what "something else" could mean), and the phrase "Mallory can now act in the name of Alice" could be specified more as "Mallory can now do anything using Alice's account that Alice could do". To illustrate this, both demonstrations will involve this type of situation.

We will now discuss these steps in more detail.

Details (Why and How)

Step 1 It might be unclear why this step is needed. Can't Mallory create s? In general, no. In some cases, the web server accepts only session IDs that it created (historically, web servers have accepted and used user-provided session IDs, but this depends on how sessions are implemented, e.g., with PHP or ASP or something else). If this is not the case, it is possible for Mallory to create s. In such cases, this step isn't necessary. However, we consider this step to increase the generality of the attack. (So, the sense of the word ``valid'' depends on whether user-provided session IDs are accepted)Now, assuming that the web server accepts only session IDs it generated, we will explain how Mallory can obtain a valid session ID. Often, as soon as a website is visited, the visitor receives a session ID, which will be present in either the URLs of pages on the website, or in a cookie. Mallory can then use this session ID as s. When websites don't give out session IDs this easily (e.g., require authentication first), then this becomes much more difficult. This will be discussed in more detail later, when we discuss how to prevent session fixation attacks, from the perspective of the web server.

Step 2 We will discuss 4 different methods of setting Alice's session ID. The first method assumes that sessions are being managed using GET parameters. The other 3 assume that sessions are managed using cookies.

- URL Copying: The session ID will leak out in the URL. Mallory can just copy one of these URLs and use it as u.

- JavaScript: If there is a vulnerable script on w which allows JavaScript to be injected, then Mallory could insert JavaScript that would set the session ID, and use the URL to the script (such that the URL, when loaded, contains the malicious JavaScript) as u.

- Meta tags: There is a type of HTML tag called a meta tag. This typically is used to supply metadata about the page (e.g., keywords for search engine indexing). However, with meta tags it is also possible to set cookies. Mallory could use the JavaScript method, changing the malicious JavaScript to a meta tag that sets the session ID. One advantage of this method is coverage. It is trivial to disable JavaScript in browsers, and for these people, the above JavaScript approach will not work. However, there doesn't appear a way of disabling the processing of meta tags by the browser (or at least there is no trivial way). So, this type of attack will work more often.

- HTTP header injection: Often, websites want to redirect users to other

pages (either on the same website, or a different one, e.g., a university

professor who has moved to a different university would change their old

web page to redirect to their new one). One way of doing this uses the

HTTP protocol. When the user makes a HTTP request to a web page, a

HTTP response message is sent back to the user. One of the fields in

this response is ``Location'' (there is also a field that can set cookies,

called ``Set-Cookie''). This is used for redirects; the value of this field

is where the user's browser should redirect to. Typically, this type of redirect

is achieved using a function in a server-side scripting language which modifies

the response fields. In PHP, for example, this would look like:

header("Location: http://newsite.com/index.php");

There is nothing particularly insecure about this. However, consider the following redirect (implemented in PHP) which redirects users to a different page on the same website:

header("Location: http://w/index.php?lang=".$_GET['lang']);

This might look fairly innocuous. However, there is a big problem with this. Consider the following URL:

http://w/index.php?lang=en%0d%0aContent-Type:%20text/html%0d%0aSet-Cookie:%20PHPSESSID=s (The %s are just the URL encoding of certain characters used in the request)

When this URL is visited, the HTTP response would have the following fields:

Location: index.php?lang=en

Content-Type: text/html

Set-Cookie: PHPSESSID=s

This sets the session ID (of the user who loaded the URL) to s, assuming that the name of the cookie corresponding to the session ID isPHPSESSID. Thus, if there is a script on the site with a redirect that incorporates user input into the new location, Mallory could use a URL similar to the above example as u.

It is important to note that this is a bug in PHP (or other server-side scripting languages). The idea is that the Location field can be terminated and that new fields can be added, much like how in SQL injections a query can be terminated and then new queries can be added. Newer versions of PHP and other scripting languages have fixed this bug. PHP doesn't allow extra fields to be injected, and ignores them, issuing a warning. In fact, the version of PHP in the Ubuntu 804 VM we used is not susceptible to this attack, and so we were unable to provide a concrete demonstration of session fixation using this technique for step 2.

Step 3 In practice, there are various ways of getting Alice to load u. Presumably, Mallory knows at least some basic information about Alice, even if it is only her email address (or some means of contacting Alice). Mallory could send Alice an email with u, and hope that Alice clicks on it. The usefulness of such an email depends both on Mallory's goal (in this case, it is just getting Alice to use Mallory's session ID, but in other cases, it might additionally include getting Alice to login) and on the knowledge of w (e.g., if Mallory knows that w sends out regular emails, Mallory could forge a convincing look-alike) as well as Alice. While this step is important, because it has more to do with social engineering than session fixation, we won't elaborate further.

As mentioned above, Mallory might want Alice to do something after loading u. In this case, the email might suggest this in a way that would not be suspicious to Alice (see the demonstrations for an example of such an email).

Of course, the message could be spread other ways than email, like using Twitter or other social networking sites, or forums, and so on.

Step 4 The phrase "act in the name of Alice" depends on what Mallory's goal is in launching this attack (e.g., the goal could be to purchase products with Alice's credit card). Clearly, at this stage Mallory is restricted to the goal in step 3 (e.g., if Alice is an admin but needs to login to admin after logging in as a normal user, and Mallory's email only succeeds in getting Alice to login as a normal user, Mallory can only do things that Alice, logged in as a normal user, can do).

Demonstrations

Installation You can obtain both demonstrations and a patched version here. We assume that the VM is configured correctly, with IP 192.168.0.100. You should copy this tarball to the Ubuntu 804 VM:scp sessionDemos.tar.gz arnold@192.168.0.100:~Inside the Ubuntu 804 VM, with cwd

/home/arnold you should

execute

Scenario There are two different demonstrations, which feature the same web application. The web application is called Amazon, and allows users to purchase products. Users can create accounts and associate a credit card number to it, allowing users to purchase products without entering a credit card number each time. Mallory's goal is to purchase things using Alice's credit card number. Thus, in addition to loading a malicious URL that will fix Alice's session, Mallory needs Alice to log in.

In both demonstrations, Alice logging in should be simulated by opening another browser and logging in with

alice:toor.Demonstration 1 In this demonstration, Amazon implements sessions using GET parameters. Notice that as soon as the site is visited, the links have a SESSID appended to them. Here are the steps:

1. Mallory visits the site and notices that the session ID appears in the URL, after browsing a bit. Mallory takes this as s.

2. Because Mallory knows that the session ID is passed as a GET parameter (from step 1), Mallory constructs the URL

http://192.168.0.100/session/index.php?query=computer&SESSID=s to

send to Alice.3. Mallory sends this URL to Alice in an email. Something like:

"Amazon has a great sale on computers! Click

Note that this is a special sale, only available to registered users."

Alice gets the email, and clicks the malicious link. No products are displayed, but Alice isn't suspicious. After all, the email said that it was only for registered users. Alice then logs in, and then clicks the link (or just manually searches for it). No products are displayed again, but Alice isn't suspicious, because she figures that she was too late (and in fact the email suggested she look at it sooner rather than latter). If this were real, then Mallory could pick something very specific as a query that returned no results but was related to computers). Note that this is more effective if Alice is interested in computers; this is an example of how information Mallory knows about Alice can be useful.

Thus, Mallory got Alice to load the URL and then login ("something else").

4. When Mallory next makes a request to the web server, Mallory will be logged in as Alice, and will be able to do whatever Alice can do. Given Mallory's goal, the "act in the name of Alice" would translate to purchasing products in the name of Alice.

Demonstration 2 In this demonstration, Amazon implements sessions using cookies. Here are the steps:

1. Mallory visits the site and notices that the site set a session ID cookie (with name PHPSESSID). Mallory takes the session ID in this cookie as s.

2. Mallory notices that the search script reflects the query back onto the page. Then, Mallory determines whether or not the script will reflect JavaScript code back onto the page. Mallory tries using <script> tags, but finds that the script doesn't reflect queries that have <script> tags. Next, Mallory finds that the script does reflect queries that have meta tags. So, Mallory constructs a query which, when reflected, sets the session ID cookie to s.

The first thing Mallory does is look at the information associated with the session ID cookie. Mallory finds the cookie's path is /, and that it expires at the end of the session.

Mallory crafts the following meta tag to set the value of this cookie:

http://192.168.0.100/session2/index.php?query=computer%3Cmeta+http-equiv%3D%22Set-Cookie%22+content%3D%22PHPSESSID%3Ds%3B+path%3D%2F%22%3EOne of the more subtle parts of this step is understanding the reason for Mallory looking at the information associated with the session ID cookie. While subtle, this part is crucial. A cookie is uniquely identified using a name, and other attributes. The cookie

PHPSESSID=s; path=/session is different than the cookie

PHPSESSID=s; path=/. Changing one won't affect the other. Without

specifying that path=/, loading u will just create a new cookie

with the name PHPSESSID.3. (This is the same as step 3 in the previous demonstration)

4. (This is the same as step 4 in the previous demonstration)

We will now discuss what in the code allowed these attacks to happen. Because Amazon consists of several pages, most of which is irrelevant to the actual attacks, we will only discuss the code that is relevant to the attacks.

Demonstration 1 - Fix Here is the relevant code which creates a session ID if the HTTP request didn't contain a GET parameter with the session ID, and which uses the session ID provided if this is not the case (this is included in each page of Amazon's website):

The provided attack of the first demonstration is easily stopped by switching to a cookie implementation of sessions. In this case, when Alice clicks the URL send by Mallory, because the session ID isn't read from the URL, Mallory will not have succeeded in fixing Alice's session ID. Since Amazon is written using PHP, the easiest way of doing this is to use PHP sessions (this is also the smartest; without any data, the likelihood that PHP will do a better job of handling sessions securely than a custom implementation is high).

We don't provide an explicit fix for this demonstration. Because the version of Amazon in the second demonstration does precisely what is suggested above, the second demonstration could be viewed as a fix for the first demonstration.

Demonstration 2 - Fix There is only one direct part of the code which is relevant for understanding how the attack provided for this demonstration succeeded:

It is also worth mentioning that it is still trivial to reflect JavaScript. Consider the attack provided in this demonstration, but instead of the malicious query there, Mallory used the query (where s is the s as used before)

Thus, it is easy to see that this demonstration allows both the JavaScript and meta tag methods to be used for setting the session ID.

To protect against this, the first change to the code would be simplifying it to:

This is enough to prevent the discussed attack. We do not provide a version of the code with only this change. Rather, the fixed version of the code implements good coding practices for session management, which will be discussed now (we will discuss the fixed version of the code afterwards).

Prevention

Please note, for better protection against session fixation, implement as many of the following as possible.Change session ID after privilege change (Best Practice) Session fixation can be largely avoided by changing the session ID after a privilege change. For example if every request specific to a user requires the user to be authenticated, an attacker would need to know the ID of the victim's log-in session. When the victim visits the link with the fixed session ID, however, they will need to log into their account in order to do anything significant as themselves. At this point, their session ID will change because their privilege level has changed (they are now logged in), and the attacker will not be able to do anything significant with the victim's previous, unauthenticated session ID.

Don't accept session IDs from GET/POST parameters (Additional Best Practice) Accepting session IDs from GET means that an attacker can perform session fixation without needing to exploit a vulnerability to set the session ID (as would be necessary in a cookie-based implementation): the session ID can be set simply by setting it in a URL. An attacker can also easily attack when session IDs are accepted from POST parameters: it is simple for the attacker to craft a form which sets the session ID when submitted by the victim. Thus, both of these session ID implementations makes it easier to perform session fixation, and so are not advised.

Use HttpOnly (Additional Best Practice) (This assumes a cookie-based session ID implementation, as recommended above) HttpOnly is an additional flag included in a Set-Cookie field in a HTTP response header. If a browser enforces HttpOnly, client side scripts (e.g., JavaScript) running in the browser will be unable to read or write cookies marked as HttpOnly. If the session ID cookie is marked as HttpOnly, this means that client side scripts cannot change the session ID (as the session ID is not exposed to the client side scripts). Thus, marking the session ID cookie as HttpOnly gives the attacker one less way of fixing a victim's session ID.

*Keep in mind that not all browsers support HttpOnly; those who use such browsers will not benefit from this practice. For example, in Safari, client side scripts are permitted to write to HttpOnly-marked cookies.

Accept only server-generated session IDs (Additional Best Practice) One way to improve security is not to accept session identifiers that were not generated by the server. This requires the attacker to obtain a session ID (i.e., step 1 in the attack diagram) generated by the web server. However, this does not completely prevent session fixation attacks: if the attacker is able to obtain a session ID, then the attacker can proceed as usual. On the other hand, this practice becomes more powerful when useful session IDs are not as easily obtained, such as when session IDs are not given out prior to some sort of authentication (the attacker might be able to authenticate, but this not be useful). Unfortunately, it is not always practical to withhold handing out session IDs until login (e.g., sessions might be used extensively before logging in), so this defense has limited use.

Applying Best Practices to Amazon The provided patched version implemented the fixes described above, as well as as many of the aforementioned session best practices as possible. These are the best practices that were implemented: using cookies instead of GET parameters, setting HTTPOnly on the session ID cookie, regenerating the session ID after changing privileges. Using cookies instead of GET parameters was already implemented, as of demonstration 2. HTTPOnly was accomplished with the following line, in

/etc/php5/apache2/php.ini:

login.php:

Exercises

- In step 2 of the attack, is it necessary for u to contain a session ID?

- Is it necessary for u to contain any GET parameters?

- In step 4 of the attack, does the web server necessarily know that s is being used by two different people?

- Does using SSL prevent session fixation?

- What is the difference between session fixation and session hijacking (e.g., through XSS, as discussed in 347)?

- In demonstration 1, is the first step (obtaining a server-generated session ID) necessary? What about demonstration 2?

- In demonstration 2, suppose that Mallory does not consider the cookie-related information when crafting the query. Will the attack still succeed? If it succeeds, will it always succeed? If it doesn't succeed, will it always fail to succeed?

- In the attack, why is it crucial that the session doesn't expire?